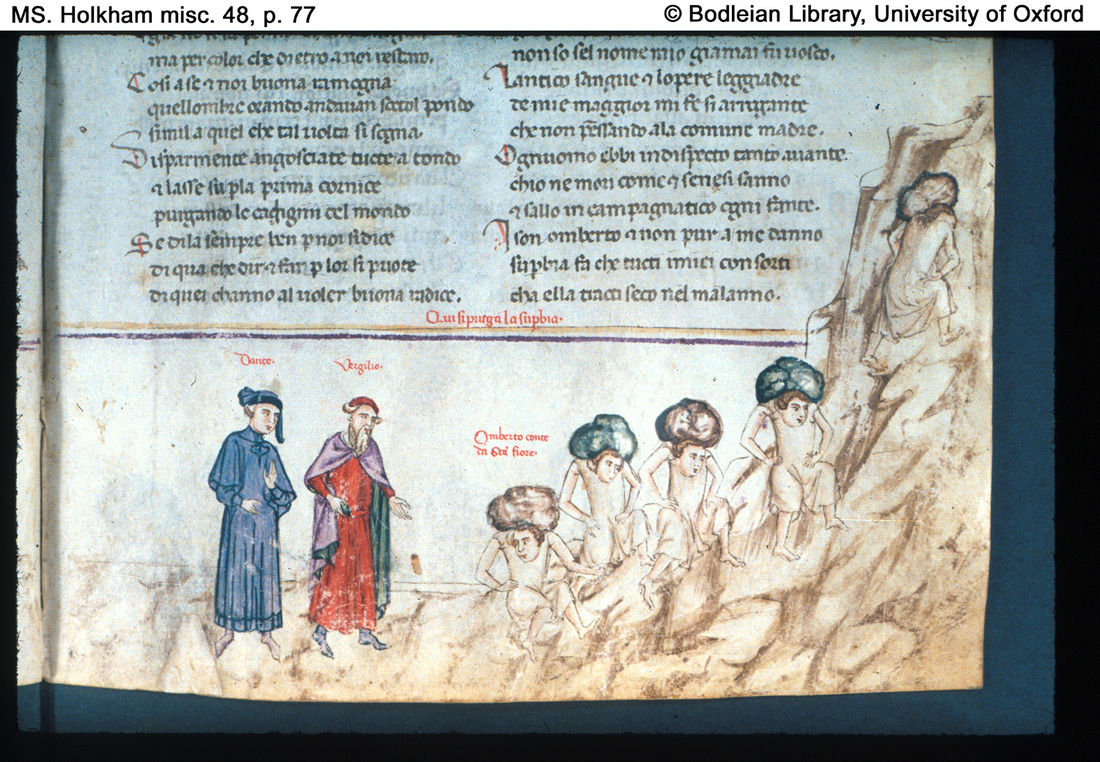

In the opening quatrains of this Canto, Dante the Poet shows how Dante the Pilgrim is obedient to his guide and mentor. In fact, Dante the Poet, like Shakespeare after him, creates a word in the Italian vernacular: pedagogo.

1 As oxen go beneath their yoke

Di pari, come buoi che vanno a giogo,

2 that overladen soul and I went side by side

m'andava io con quell' anima carca,

3 as long as my dear escort granted.

fin che 'l sofferse il dolce pedagogo.

The term comes originally from the Greek in Galatians 3:23-24, where Paul refers to the Law as formerly being a guide or tutor. It has come to us in English as a teacher or guide of boys, originally. However, in this Canto it is obviously being used as a wise spiritual mentor that urges Dante the Pilgrim further on his journey toward repentance, redemption and wholeness. Dante the Pilgrim admits that he felt the need to “remain bowed down and shrunken” [v.9], he followed the advice in complete obedience: “I set out, following gladly…” [v. 10].

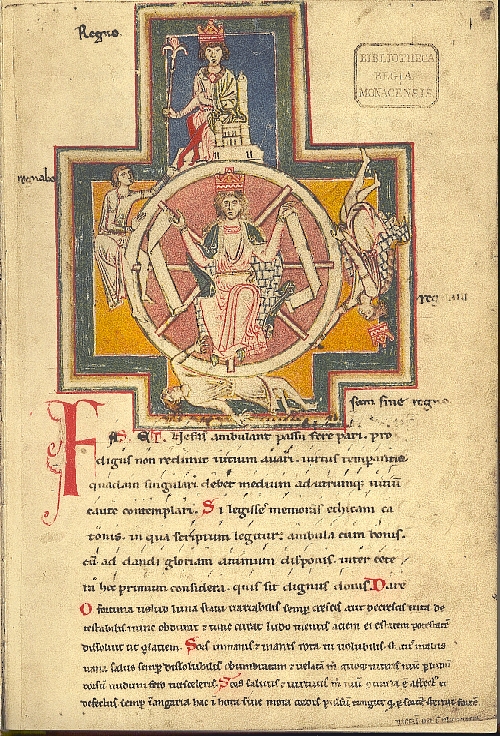

A ‘pedagogo’ or wise guide is needed to progress in spiritual formation and wholeness. We often do not know what is best for ourselves, and are attracted at times to the very things that will hinder or destroy wholeness and redemption. The spiritual writer Tanquerey puts it like this: “Progress in holiness is a long and painful ascent over a steep path bordered by precipices. To venture thereon without an experienced guide is highly imprudent.” This is not only true for mountain climbing (whether that mountain be the Seven Story Mountain of Purgatory or a ‘fourteener’ in Colorado) but it is also true in our own spiritual journey.

The difficulty, of course, is that we can’t see ourselves very clearly and often the way to go in our journey toward wholeness is twisted and uncertain. We cannot be wise guides for ourselves. Frances de Sales writes: “We are unable to gaze eye to eye upon ourselves, we cannot be impartial judges in our own case, by reason of a certain complacency, so veiled, so unsuspected that the keenest insight alone can discover its existence; those who suffer from it are not aware of it unless someone points it out to them.” St. Bernard of Clairvaux puts it bluntly: “whoever constitutes himself his own guide, becomes the disciple of a fool.”

We’ve looked at this earlier and will most certainly visit it again, but it remains a needed and necessary lesson. Dante the Poet’s usage of ‘pedagogo’ and Dante the Pilgrim’s open admission that his guide knows best is Good News, if hard news, for 21st century Americans. We continue to resist obedience and guidance from outside authorities in the area of spiritual growth. And of course, the choice of guide, in whom one is going to follow obediently, is crucial. I remember my father telling us with a wry smile of crossing La Veta Pass at night in a blinding snowstorm. It was so fierce that he could barely see the road. He saw some tire tracks that were clearly marked out and decided to follow them, which he did, faithfully. And he ended up following them right off the road into the ditch; both cars side by side in the snowstorm. We must choose our guides wisely.

This is the third Canto on the sin of Pride which requires the virtue of Humility in order for the first ‘P’ to be erased from the forehead of Dante the Pilgrim. In Canto X we were given three examples of Humility:

1-The Annunciation and Mary’s humble submission;

2-King David humbling himself by dancing with joy as the Ark of the Covenant is returned;

3-The Emperor Trajan stopping his entire army to assure justice is done for a poor widow.

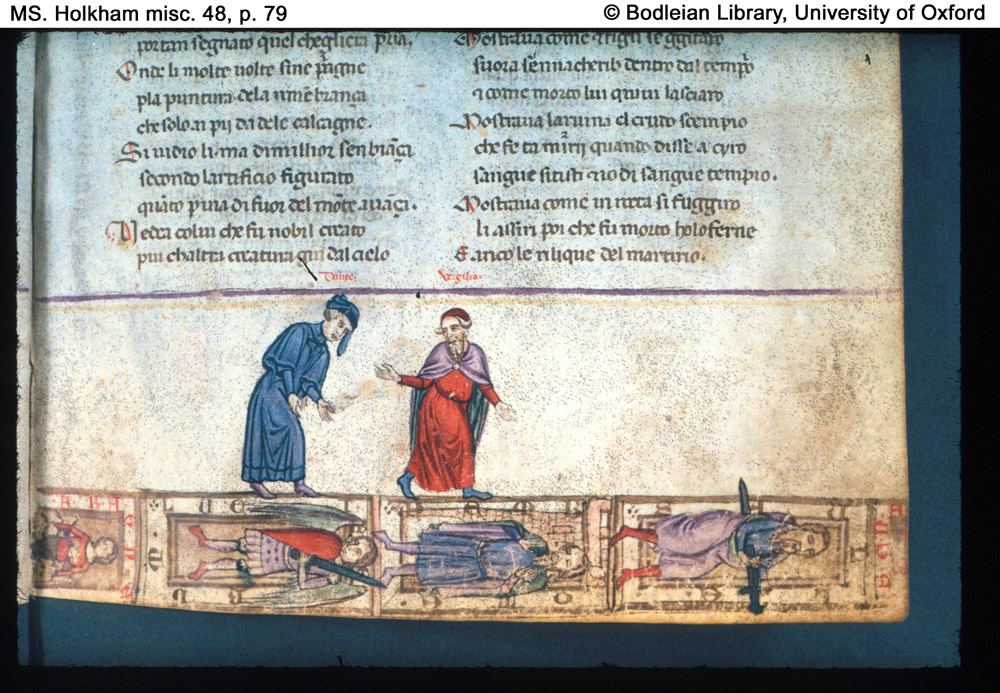

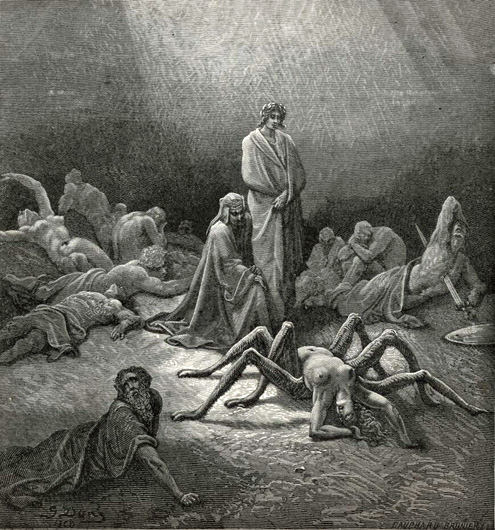

Three and only three examples are given for Humility. However, to show the consequences of the sin of Pride, we are given three times that many when they are carved into the walkway on the far side of this level. Is this, I wonder, a not so subtle recognition that true humility is far more rare in real life than all the examples of overweening Pride? Is this a recognition that often the villains and the sinners are more interesting than those who never go astray? [For instance, the examples of Arachne's pride resulting her turning into a spider, and Judith administering the stroke of punishment to Holofernes for his pride... See images below...] To these questions, I'd say: YUP.

127 Then I did as those who go along,

Allor fec' io come color che vanno

128 with something on their head, unknown to them,

con cosa in capo non da lor saputa,

129 except the acts of others make them wonder,

se non che ' cenni altrui sospecciar fanno;

130 so that they reach up with their hand for answers.

per che la mano ad accertar s'aiuta,

131 Touching and searching they accomplish

e cerca e truova e quello officio adempie

132 the task that sight cannot achieve,

che non si può fornir per la veduta;

133 and, spreading the fingers of my right hand,

e con le dita de la destra scempie

134 I found that, of the seven letters he of the keys

trovai pur sei le lettere che 'ncise

135 had traced upon my forehead, only six remained.

quel da le chiavi a me sovra le tempie:

136 Observing this, my leader smiled.

a che guardando, il mio duca sorrise.

Look what you’ve done, Dante the Pilgrim, AND YOU DIDN’T EVEN KNOW IT!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed