We come now to the exact center of the Commedia, and it is momentous. Dante the Poet and Dante the Pilgrim seem to fuse at this point, addressing each individual who has ever journeyed with both to this Canto XVII: “Remember, O Reader…” The two most crucial qualities in the Commedia are lifted up in this Canto: Imagination and Love… and Imagination is addressed first.

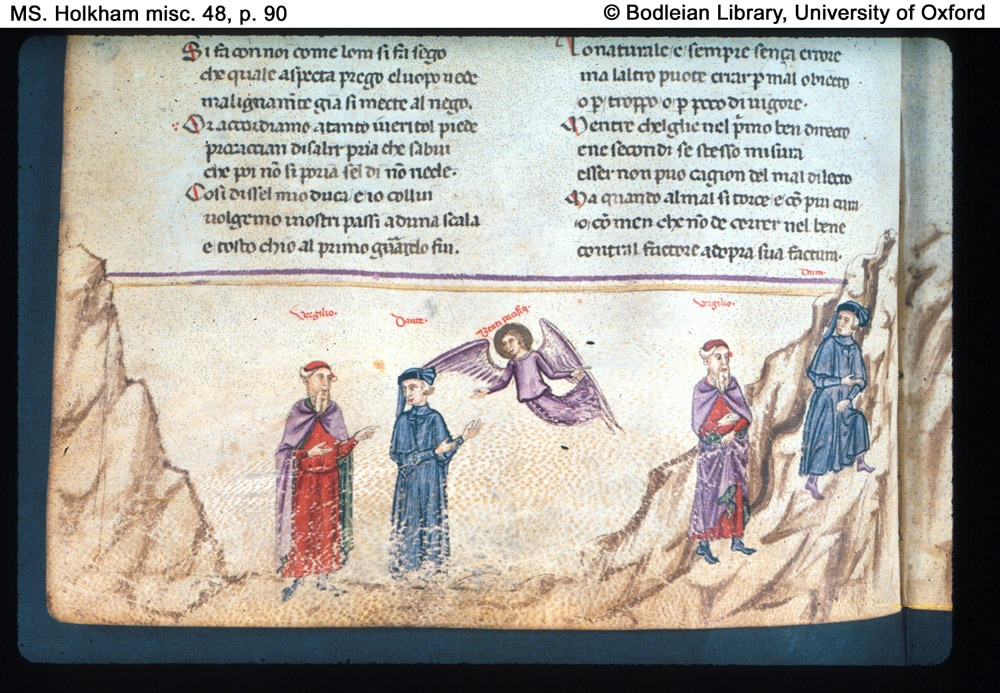

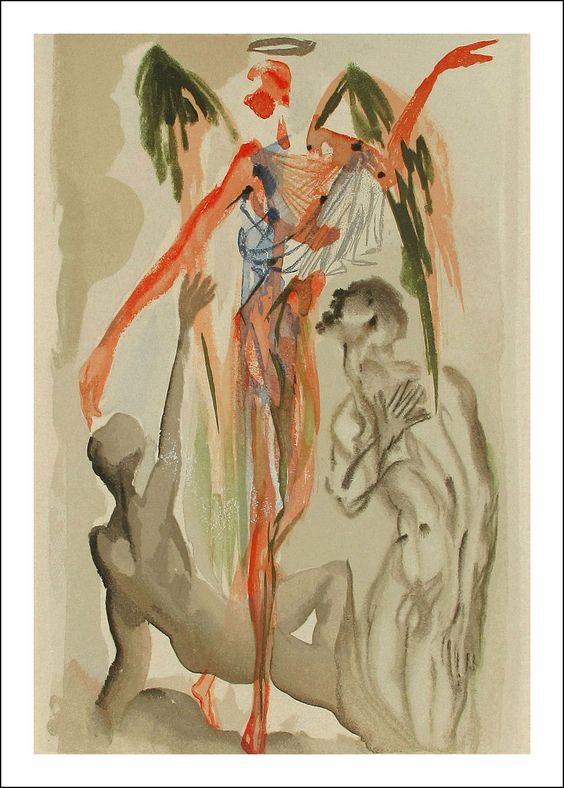

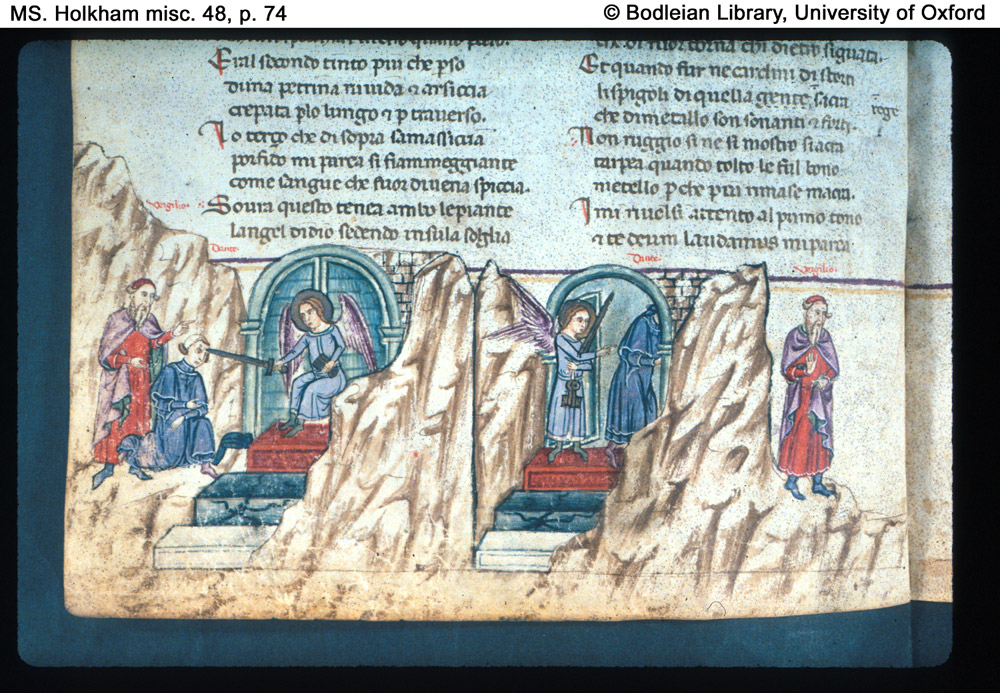

As Virgil and Dante the Pilgrim move toward the steps that will lift them to the next level of Purgatory, we are ushered into a world of fantasy and imagination. Lines 13 – 18 give us insight into the creation of the entire Commedia with a realization that the imagination can be a gift of sacred creation that may have little to do with our current reality. It may come from within or it may be sent by the Holy Spirit, but it is that which can set our entire lives into motion and toward unexpected futures.

13 O imagination, which at times so rob us

O imaginativa che ne rube

14 of outward things we pay no heed,

talvolta sì di fuor, ch'om non s'accorge

15 though a thousand trumpets sound around us,

perché dintorno suonin mille tube,

16 who sets you into motion if the senses offer

chi move te, se 'l senso non ti porge?

17 nothing? A light, formed in the heavens, moves you

Moveti lume che nel ciel s'informa,

18 either of itself or by a will that sends it down.

per sé o per voler che giù lo scorge.

Dante the Pilgrim is ushered into the three visions that are the Scourge of Wrath: the Biblical, mythological and historical examples when wrath led to destruction and despair. These visions are so vivid that he is completely entranced by each one to the extent that he is completely unaware of what is happening about him in the “real world,” even if there were “a thousand trumpets” that were sounding in his ear.

But there is also a parallel lesson from this opening in Canto 17 that applies to the writing of this entire creation of the Commedia. We have in the Commedia that which acts as those soap bubbles of visions which “moves [us] either of itself or by a will that sends it down.” This entire work is a creation of the imagination, and indeed, there are certainly questions as to its origin; whether from God, or the muses or from within Dante the Poet himself only, it sets us into motion and changes our lives. We may be removed from our current reality during the time we are reading this great poem, just as Dante the Pilgrim is removed from his present surroundings during the time of each vision, and yet the lessons learned and the experience of each ‘fantasia’ will and should have a vital impact on our lived reality once we put the book down or the vision is complete. Lessons can be learned from this “lofty phantasy” that is the Commedia, and in fact, from any great work of imagination. My fear is that many of us allow our present reality to dictate our emotional state of despair and cynicism and we refuse anything that might lift us out of our current reality. There are visions / lessons from great and creative works of imagination that can lift us and help us continue the journey of growth and transformation into wholeness and holiness if we would read them with a sympathetic and open spirit. If the only thing we believe in or trust is the daily news, we among all peoples, are the most to be pitied. It is no wonder depression, fear and cynicism rules our current culture and worldview.

We journey now, after the removal of the “P” of Wrath from Dante the Pilgrim’s forehead, toward the next level of Purgatory. Yet once the sun sets, there is no more movement on the entire mountain: rest and contemplation are enforced, being just as important as movement and achievement. However, Dante the Pilgrim is eager to grow and learn more to such an extent that he yearns to journey in knowledge even if he can no longer journey further up Mount Purgatory.

81 Then I turned to my master and I said:

poi mi volsi al maestro mio, e dissi:

82 'Sweet father, tell me, what is the offense

"Dolce mio padre, dì, quale offensione

83 made clean here in this circle that we've reached?

si purga qui nel giro dove semo?

84 If our feet must rest, do not arrest your words.'

Se i piè si stanno, non stea tuo sermone."

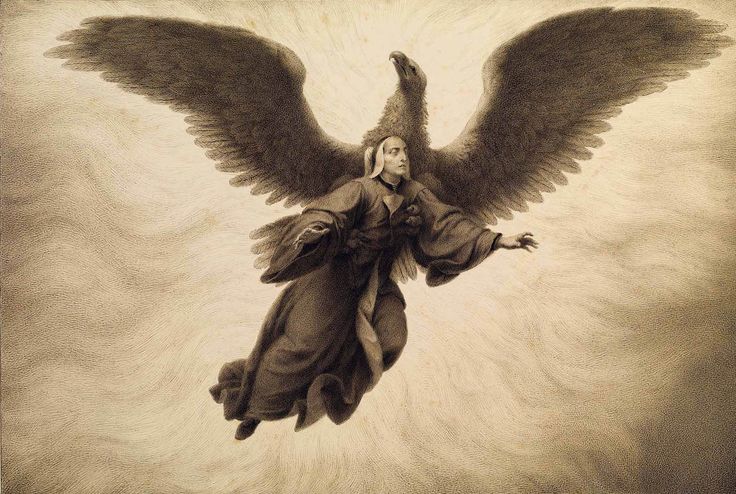

Virgil explains that they are now at the level of Sloth and agrees to teach Dante the Pilgrim by explaining the second of the two themes. The first was Imagination and now we look at Love, which is the very foundation of the Commedia and the entire Medieval Worldview. There are two types of Love in God’s created order. The first is “natural” love which is to be found among all creation. An example of this is found in St. Francis of Assisi. His Canticle of the Sun celebrates the fact that all creation sings praise to the Creator, and can’t help but do so. There is, however, another type of Love which is measured by rationality and intention. In different translations of the Commedia, this Love is called “rational,” “elective,” or “mental.” The crucial point is that this type of Love defines the Seven Deadly Sins and helps form the Seven Storey Mountain as a result.

94 'The natural is always without error,

Lo naturale è sempre sanza errore,

95 but the other may err in its chosen goal

ma l'altro puote errar per malo obietto

96 or through excessive or deficient vigor.

o per troppo o per poco di vigore.

Love, surprisingly, is at the heart of every action, whether good or bad and this clarifies the map of the entire Purgatorio… hence this Canto has an arrow pointing to the terrace of Sloth with the words “You Are Here.” Elective or Rational Love defines the sins and consequences of these choices and actions. In line 95 we read that choosing the wrong goal to love can lead to sin. Misdirected love can lead to Pride or Envy or Wrath, the first three levels of the Purgatory. Line 96 completes the map; deficient vigor in Love is Sloth [their current level]. Avarice, Gluttony, Lust are the sins that result from excessive vigor in loving the wrong things which gives us the last three levels. The rest of the Canto expands on this insight, that how we choose and use Love forms the morality and integrity of our lives. As opposed to the Inferno, where actions are punished, intentions are primary in the Purgatorio. Virgil expands his statements further in the rest of this Canto.

97 'While it is directed to the primal good,

Mentre ch'elli è nel primo ben diretto,

98 knowing moderation in its lesser goals,

e ne' secondi sé stesso misura,

99 it cannot be the cause of wrongful pleasure.

esser non può cagion di mal diletto;

100 'But when it bends to evil, or pursues the good

ma quando al mal si torce, o con più cura

101 with more or less concern than needed,

o con men che non dee corre nel bene,

102 then the creature works against his Maker.

contra 'l fattore adovra sua fattura.

It was Augustine of Hippo in the ‘City of God’ who helped describe this Christian understanding of Love:

City of God: 14:7

…a right will is good love and a wrong will is bad love.

…recta itaque voluntas est bonus amor et voluntas perversa malus amor.

Aquinas expanded this definition of ‘bonus amor’ and ‘malus amor’ in helpful and important ways in his treatise on the passions:

…every agent whatsoever, therefore, performs every action out of love of some kind.

…Unde manifestum est quod omne agens, quodcumque sit, agit quamcumque actionem ex aliquo amore.

This is remarkably helpful to find at the exact center of the Commedia in that we can look back, for instance, at the different relationships in the Inferno that were justified in the name of “Love,” but they were, in fact, Love used incorrectly. This is what Augustine would call “malus amor” forgetting that, as Virgil reminds us, Love “cannot be the cause of wrongful pleasure.” This clarifies much when we read of the supposed love of Francesca da Rimini for her lover Paolo in Inferno 5, or comparing the love of Cavalcanti for his son with the love of Farinata for Florence in Inferno 10. Even Ulysses’ doomed love for learning and discovery is set in its proper context in Inferno 26, for according to this paradigm, he had no proper love he was without proper moderation and had even less discernment. This, of course, leads us all the way back to the Golden Mean of Aristotle too…

The Beatles obviously had not read this Canto! Love misused and misdirected or even misplaced will not lead to a whole and holy life. Indeed, the misuse of love will more often than not lead to the abuse and misuse of other human beings, those beloved ones made in the image of God and for whom Christ died. We will be looking at these concepts further in the Commedia, but let me stay a moment more on the level of Sloth before signing off. Let’s remember that there is a priority of place in Dante’s universe. Sloth is where it is due to its placement between the lower and greater sins Pride, Envy and Wrath and the ‘lesser’ sins further up the mountain, Avarice, Gluttony and Lust. The sins below Sloth destroy others and community. The sins above Sloth represent the immoderate love of good things which should be secondary in one’s life, basically destroy oneself. Food or sex or material wealth are not evil in and of themselves. It is only when they take the place of God the Lover and Creator that they become sinful. Robert Hollander notes, “By failing to respond to God’s offered love more energetically, the slothful are more rebellious to Him than are the avaricious, gluttonous, and lustful… .” Indeed. Here is where Aristotle’s golden mean becomes a bit jaded and stale. God is looking for more than just those who won’t make mistakes or don’t act fiercely and lovingly, even if in the wrong direction. None of the commentaries I read had this Biblical quote, but it belongs here:

Revelation 3:16: “I know your deeds, that you are neither cold nor hot; I wish that you were cold or hot. So because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of My mouth.”

I suppose if I had my ‘druthers’ I’d rather be guilty of being to passionate and foolhardy in my loves than to never have loved fiercely at all.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed