The conversation between the poets continues and will continue in the remaining Cantos. Some commentators have spilled much ink on the importance of poetry and philosophy that is shared in these conversations. We will surely get to that at some point. One of the central themes I wish to lift up here, however, is the issue of unexpected influence and unknown guidance / mentoring. Virgil and Dante the Pilgrim learn that Statius was, in fact, profoundly influenced by Virgil. First and foremost, of course, was impetus to become a poet himself, set by the power and beauty of the Aeneid of Virgil.

64 And the other answered him: 'It was you who first

Ed elli a lui: "Tu prima m'invïasti

65 set me toward Parnassus to drink in its grottoes,

verso Parnaso a ber ne le sue grotte,

This is a classical reference which states that it was Virgil’s Aeneid that led him to drink of the water of inspiration given by the muses on Mt. Parnassus to classical poets. This is to be expected and was, in fact, assumed in Dante’s time that Virgil and Statius were the two great classical poets of Rome.

And yet, we never know the extent to which our actions and statements affect and influence others who are watching, who are listening, who are the recipients of our love or anger or dismissive rejection. Statius tells them that, in fact, Virgil was also a spiritual guide, saving him in two different ways. The first was slipped in on us in lines 37-39.

37 'And had I not reformed my inclination

E se non fosse ch'io drizzai mia cura,

38 when I came to understand the lines in which,

quand'io intesi là dove tu chiame,

39 as if enraged at human nature, you cried out:

crucciato quasi a l'umana natura:

40 '"To what end, O cursèd hunger for gold,

'Per che non reggi tu, o sacra fame

41 do you not govern the appetite of mortals?"

de l'oro, l'appetito de' mortali?',

42 I would know the rolling weights and dismal jousts.

voltando sentirei le giostre grame.

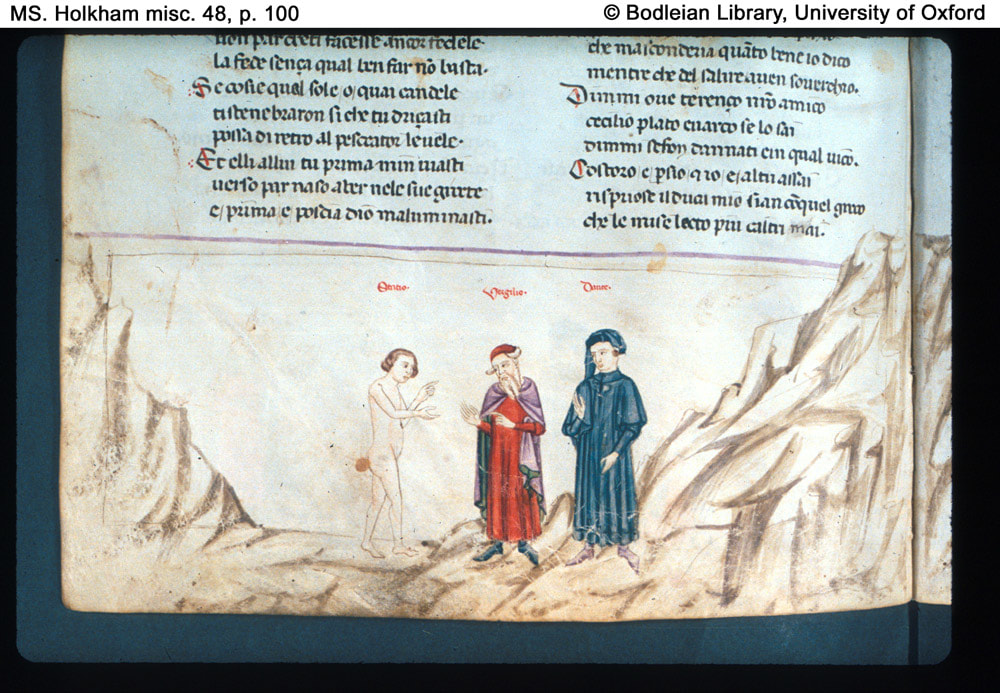

Dante following behind the two poets in Botticelli's drawing of Canto XXII

Dante following behind the two poets in Botticelli's drawing of Canto XXII 66 and you who first lit my way toward God.

e prima appresso Dio m'alluminasti.

67 'You were as one who goes by night, carrying

Facesti come quei che va di notte,

68 the light behind him--it is no help to him,

che porta il lume dietro e sé non giova,

69 but instructs all those who follow--

ma dopo sé fa le persone dotte,

We find the gift of Virgil’s Aeneid as well as the limitations of Virgil as guide. Dante surely acknowledges that he, like Statius, was guided by the light of Virgil’s creativity and power. And yet, the light guides those who come after him while he walks in the dark toward Limbo. Dante the Pilgrim will need a new guide soon and Statius is the precursor of the one to come: Beatrice.

Dante the Poet continues to surprise and shock modern sensibilities by refusing to condemn along doctrinal party lines. In essence, Dante the Poet creates a scenario where the text of secular poetry is the lure and link into sacred life and reality. There is a true sense that wherever there is beauty, integrity and truth then God is to be found within that context, regardless of the origins of the text or the age in which it has been written. Augustine of Hippo, Thomas Aquinas and others embraced this approach to the classical poetry and philosophy of former ages. Hence the appreciation of both Plato and Aristotle by Christian Fathers and Mothers. Some of the secular and classical scholars attempt to state that Dante was not really a Christian at all due to his usage of classical themes, mythology and Aristotelian philosophy. Dante, however, will not be classified in such a simplistic manner. His embrace of the mystery of God’s love and acceptance is expansive and surprising.

Dante the Poet is in good company here, and has learned his lesson well. Augustine of Hippo in Book II recognizes this in the title of Chp. 18: “No Help Is To Be Despised Even Though It Come From A Profane Source.” In the chapter he states specifically “we ought not to refuse to learn letters because they say that Mercury discovered them; nor because they have dedicated temples to Justice and Virtue, and prefer to worship in the form of stones things that ought to have their place in the heart, ought we on that account to forsake justice and virtue. Nay, but let every good and true Christian understand that wherever truth may be found, it belongs to his Master…” Thomas Aquinas embraced this, bringing the truths and insights of Aristotle into his work. It has been said that all truth is God’s truth, but that embrace presupposes, of course, the presupposition that there is a loving God who creates and cares about our finding and embracing truth.

John Calvin recognized this and in Book II of his Institutes he speaks of accepting the gift of the sciences even though the insights may come from pagan and secular writers. “Whenever we come upon these matters in secular writers, let that admirable light of truth shining in them teach us that the mind of man, though fallen and perverted from its wholeness, is nevertheless clothed and ornamented with God’s excellent gifts. If we regard the Spirit of God as the sole fountain of truth, we shall neither reject the truth itself, nor despise it wherever it shall appear, unless we wish to dishonor the Spirit of God.” In our own time, C. S. Lewis and his beautiful “Till We Have Faces” and the Four Quartets of T. S. Eliot embrace the powerful presence of God’s truth in the greatest of the classical worldview and mythology. So too for Dante.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed