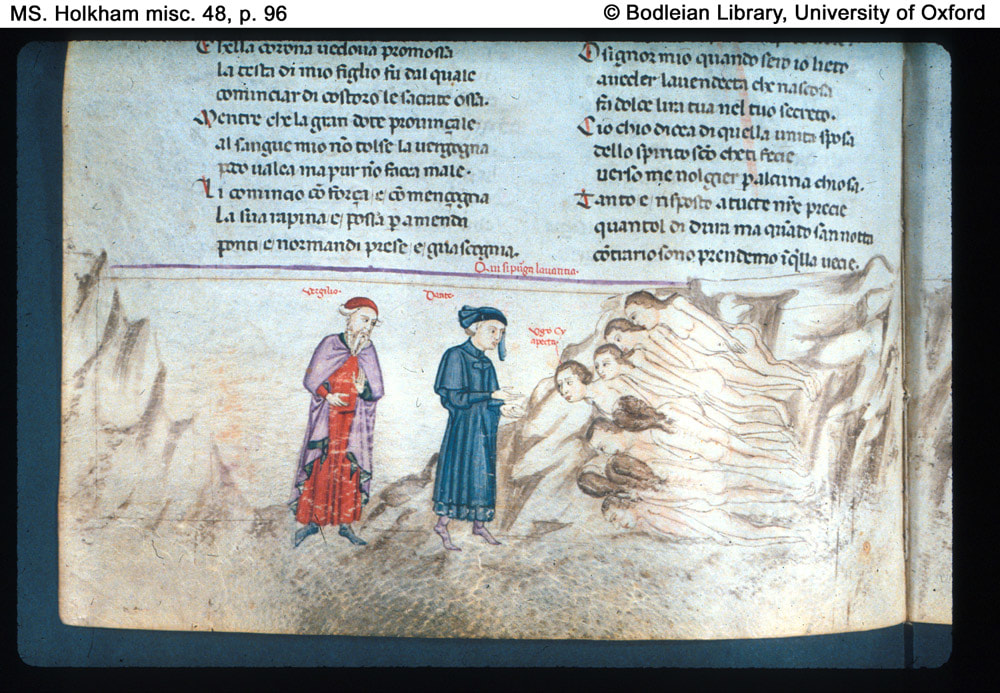

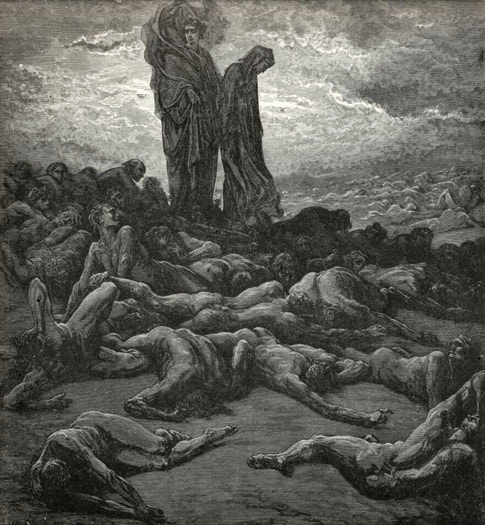

In these last few Cantos we have slowed down to a crawl, or at least a stroll, what with interactions with poets, friends and the resulting fellowship. Virgil and Statius have been embracing, hobnobbing and catching up on the status of past poets, and soon, Dante will be discovered by his own dear friend, Forese. We have come to a complete halt, almost like during a walk in the park and stopping to view the trees or birds or flowers: a leisurely and, well, lazy interlude. Dante the Pilgrim admits to it with his recognition that he is stopped, gazing for the source of voices, in a “wasteful way…”

1 While I was peering through green boughs,

Mentre che li occhi per la fronda verde

2 even as do men who waste their lives

ficcava ïo sì come far suole

3 in hunting after birds,

chi dietro a li uccellin sua vita perde,

Virgil, in fact, seems to realize that they indeed have been remiss in these last few Cantos and urges him to better use of time. In doing so, he admits that perhaps he too has not made the best use of time.

4 my more than father said to me: 'My son,

lo più che padre mi dicea: "Figliuole,

5 come along, for the time we are allowed

vienne oramai, ché 'l tempo che n'è imposto

6 should be apportioned to a better use.'

più utilmente compartir si vuole."

And yet, we are reminded in Sayers’ commentary that there is wasteful time, and there is useful time, noting that now Dante the Pilgrim follows close behind the two poets, but still doing nothing other than listening and learning. This is time well spent. “every step I took paid double wages.” L. 9 [Sayers]

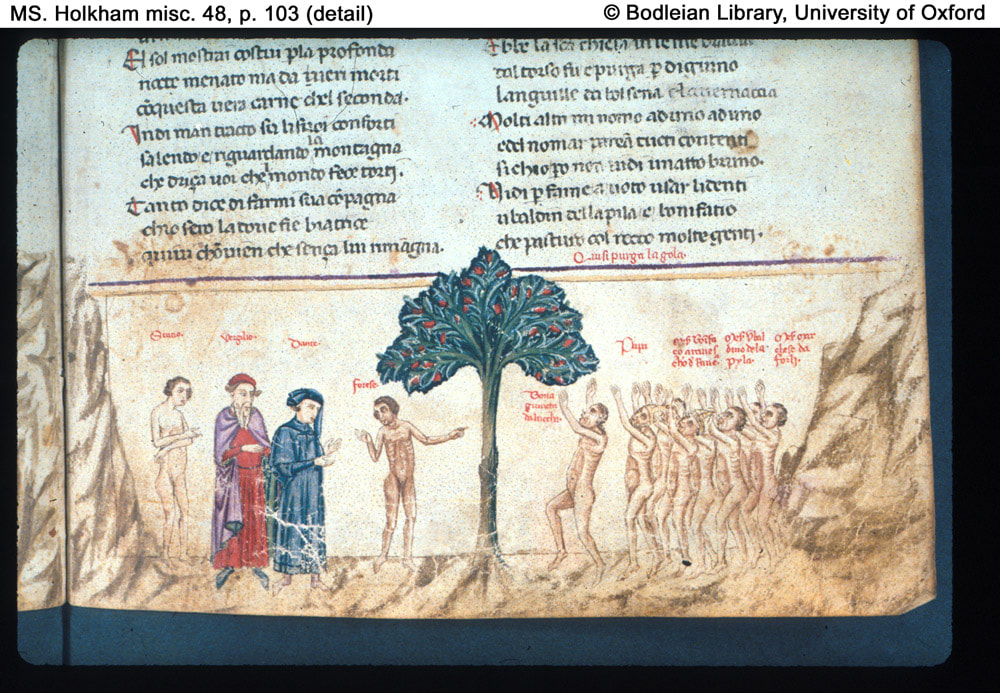

The differences in the SPAN of years or time is highlighted here too, as can be seen in the principal actors and friends in this Canto. Statius has just been released from the Seven-Storey Mountain after hundreds of years while Forese is close to the top after only four years since his death. Of course, Forese is aided by the prayers of his holy wife, Nella. Books have been written about the role played by Time here on Mt. Purgatory. It is only at this intermediate, transitional stage of Dante’s version of the medieval worldview that sleep is experienced and dreams interpreted. That requires time. And we see that it is not just action that matters, but presence, intention, patience and a hungry heart. While eternity is the paradigm for the Inferno and Paradiso, however here on this mountain, Time is the necessary vehicle, the currency, by which each soul is not only measured, but redeemed.

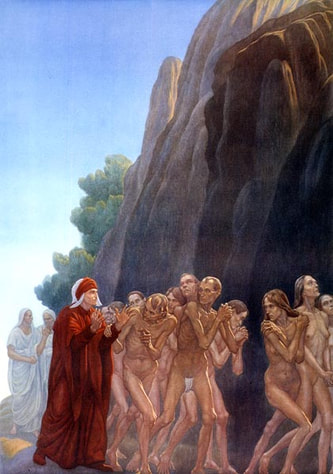

Amos Nattini

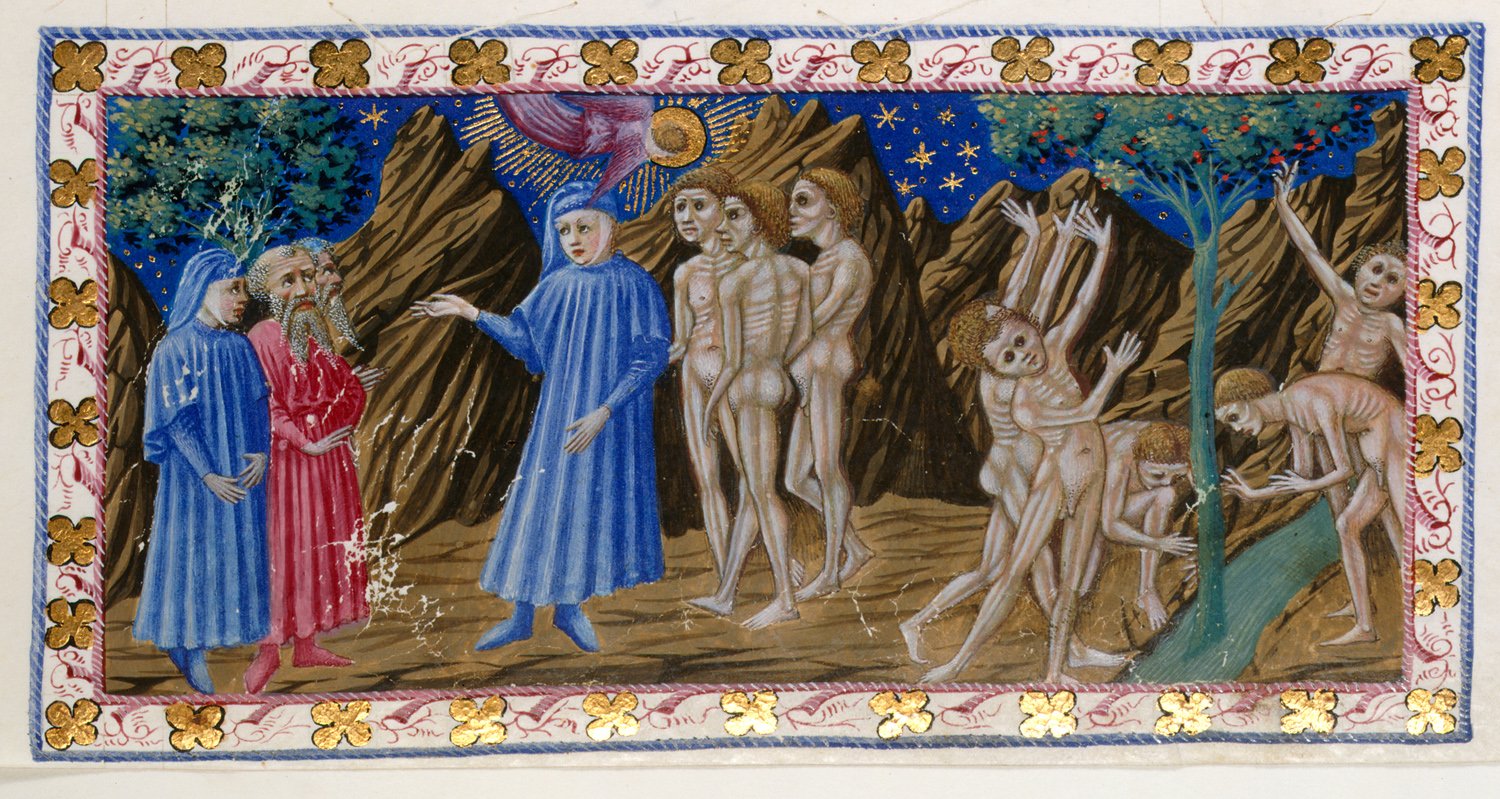

Amos Nattini On this level of the Penitent Gluttons, we find examples of the proper and improper use of one’s mouth which reflects one’s proper and improper desires/hungers. The best thing for these Penitent Gluttons is to open their lips and sing God’s praise.

11 'Labïa mëa, Domine' in tones

"Labïa mëa, Domine" per modo

12 that brought at once delight and grief.

tal, che diletto e doglia parturìe.

The opening hymn of Lauds rings out as the active repentance of the penitent Gluttons: 'O Lord, open my lips, and my mouth shall proclaim your praise.' Psalm 50:17 has as its context the repentance of David for his excessive lust, a type of gluttony one might say, but the true point is that our mouths and bodies should not be focused on self-referent hungers and pleasure only. We are then given the negative examples of the WRONG ways to use one’s mouth and hungers, as in devouring one’s own flesh [Erysichthon] and one’s own children [Mary of Jerusalem]. In all these cases, the mouth opens, but for far different reasons. We are even given the opening of Christ’s lips to cry out “Eli! Eli!” from the Cross, but the point is not the openness of the lips, but the hunger of the heart, yet again. Christ is hungry for redemption. The penitents are hungry for repentance. We see, in fact, the praise of Nella’s prayers as she opens her lips to pray for Forese and her broken and hungry heart on the behalf of her beloved.

This hunger of the heart is the reason that suffering is embraced and seen as a gift and grace.

72 I speak of pain but should say solace,

io dico pena, e dovria dir sollazzo,

73 'for the same desire leads us to the trees

ché quella voglia a li alberi ci mena

74 that led Christ to utter Elì with such bliss

che menò Cristo lieto a dire 'Elì,'

75 when with the blood from His own veins He made us free.'

quando ne liberò con la sua vena."

The willingness to suffer is weighed against the redemption which results from that willing acceptance of it. Christ’s hunger for our redemption and salvation is seen as an act of love and joy, ultimately heard in His cry from the Cross: “It Is Finished.” The penitents true and appropriate hunger is the hunger for holiness and for God, and is seen by their willingness to suffer. This is truly a counter-cultural lesson for the 21st century.

Throughout the various levels of Dante the Poet’s universe, we have seen a kaleidoscope of emotions, justifications and reactions. Depending on the level in which one finds oneself, these can change, from anger and self-righteousness in the Inferno to sorrow and repentance in the Purgatorio to praise and wonder in the Paradiso. However, having read The Commedia several times over the span of 30 years, I have found one reality that seems to be a constant on every level of reality for Dante the Poet: Curiosity. Whether one is in the depths of Hell or on the slopes of Purgatory or at the heart of Paradise, Curiosity is present. Dante’s characters want to discover and discuss and discern, regardless of their state in the afterlife. Why is Dante the Pilgrim here? What has happened to my loved ones on earth? How does this help your passage through eternity? How did my writings lead you to salvation? Why did I dream that specific dream?

Curiosity may have killed the cat, but in Dante’s universe, curiosity defines the human condition. Therapists and counselors know that the presence of depression is authentic when curiosity dies. The heart of scientific discovery is based on curiosity. As we climb further we have seen that this curiosity needs to be directed toward a greater good and more mature soul. Dante the Pilgrim peering into the branches of the tree is “wasting” time, and his curiosity needs to be “apportioned to a better use.” So it is, by following and listening yet again to his two guides. As I said above: this is time well spent. “every step I took paid double wages.” L. 9 [Sayers] My fear, at times, is that in our present culture today, whether in higher education or spiritual formation or political discourse, curiosity is crushed. Doctrine, dogma, lack of dialogue and lack of discovery rule the day. Open respect and curiosity about another’s point of view or daily struggle are hard to find any longer. I am impressed that Dante the Pilgrim is willing to talk with and listen every single character he finds on his journey: caring curiosity incarnate.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed