The desire of Dante the Pilgrim to learn, know and grow continues apace, as we’ve noted in the last few cantos. While Statius and Forese have provided opportunities to speak of and celebrate art and poetry, it ultimately comes down to the creative impulse and Dante the Pilgrim’s desire to know more about it all, the reality in which he lives and moves and has his being on this seven story mountain. This is shown in a lively and lovely little simile where Dante the Pilgrim wants to ask questions, but is hesitant, continually opening and shutting his mouth without speaking a word.

10 And as a baby stork may raise a wing,

E quale il cicognin che leva l'ala

11 longing to fly, but does not dare

per voglia di volare, e non s'attenta

12 to leave its nest and lowers it again,

d'abbandonar lo nido, e giù la cala;

13 such was I, my desire to question kindled

tal era io con voglia accesa e spenta

14 and then put out, moving my mouth

di dimandar, venendo infino a l'atto

15 as does a man who sets himself to speak.

che fa colui ch'a dicer s'argomenta.

Virgil finally says, dude, go ahead and ask away, what is on your mind and heart? Indeed, after all, the very reason for this journey through the medieval universe is to learn and grow in one’s own spiritual formation. Unlike Paolo and Francesca or Ulysses in the Inferno, this is the right way and the appropriate reason to be ever-curious: how does one follow love, why do the penitent shades actually change their being as they grow more repentant and loving, can poetry and art contribute to this redemption of the soul?

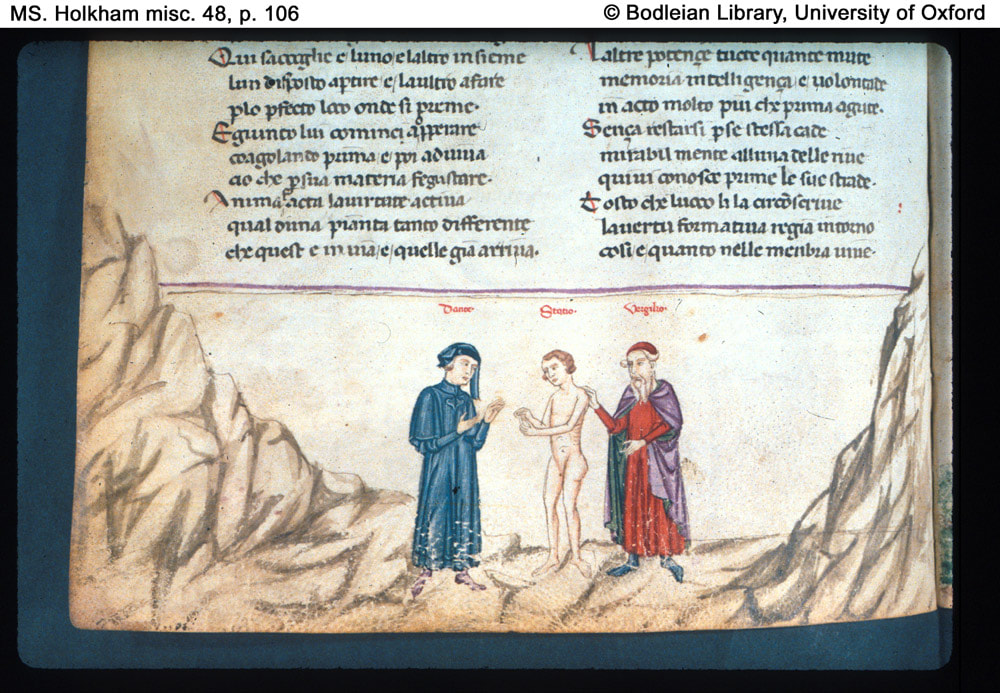

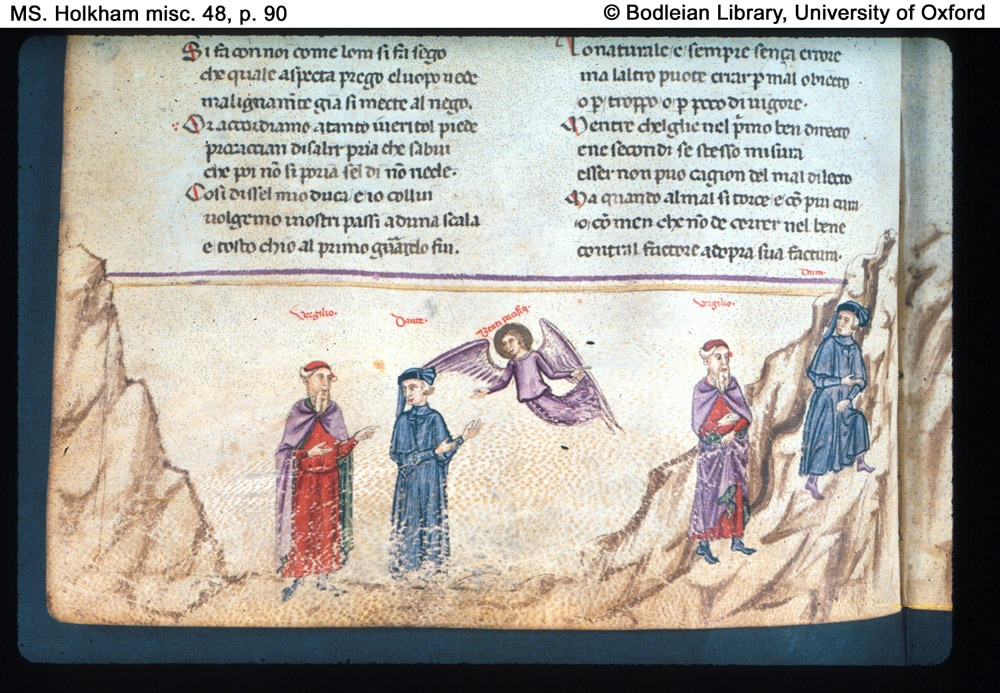

Dante the Pilgrim wants to know why these shades, who don’t have physical bodies, change so radically in their appearance as in the hollow eyes and emaciated appearance of Forese, who is recognizable only by his voice. Virgil mentions briefly the parallel reality of the life of Meleager with the length of time it takes to burn a log or the copied actions of in a mirror. These may or may not help the modern mind to understand the simile, but the extended explanation by Statius about medieval embryology needs to be read in the context of these three cantos on poetry and creativity: 24, 25, and 26. My three main sources: Dorothy Sayer, John Ciardi and John Hollander all move in different directions to explain this odd excursus on the creation of life. The discourse of Statius is divided up into three parts:

1. The Nature of the Generative Principle [31-51]

2. The Birth of the Human Soul [52-78]

3. The Nature of Aerial Bodies [79-106]

We cannot go fully into the science of medieval biology, but we need to remember that blood was the active vital force in all bodily actions. It was thought that a mother’s milk from the breast contained blood, along with the assumption that blood formed part of the male ejaculation during intercourse. [“it descends where silence is more fit than speech and from there later drops into the natural vessel on another's blood.”] It was there that blood from the male joined with blood from the female to create life. There are many commentaries that will help you understand this medieval embryology in better detail. At the end of line 51, we have a nascent human being, an embryo, but, as yet, without a soul. As the fetus develops in nature, God celebrates and instills a rational, yet eternal soul in the body that has grown in the womb through the stages of plant [feeling], animal [sensual], finally to the image of God [spiritual].

Ultimately, like Aquinas, Dante the Poet uses Aristotelian terms and science to help medieval Christians understand their world. Prue Shaw does a wonderful job in explaining this in her book Reading Dante; “Aristotle’s account of the great chain of being places human beings above plants and animals in the natural order. Yet human existence presupposes and includes the qualities and capacities of plants [plants are alive] and of animals [animals have sensation…].” Humans have a third quality, given by God, to reflect on one’s self, to be rational. It all is summed up succinctly by Dante:

74 all it there finds active and becomes a single soul

in sua sustanzia, e fassi un'alma sola,

75 that lives, and feels, and reflects upon itself.

che vive e sente e sé in sé rigira.

Unlike many today, Dante has the capacity to celebrate and utilize secular science, classical poetry and theological reflection, all in the same canto. And ALL of this is to emphasize and explore the creative process, not only in nature, but in art as well. God, the Creator celebrates creativity in us as well, at every level.

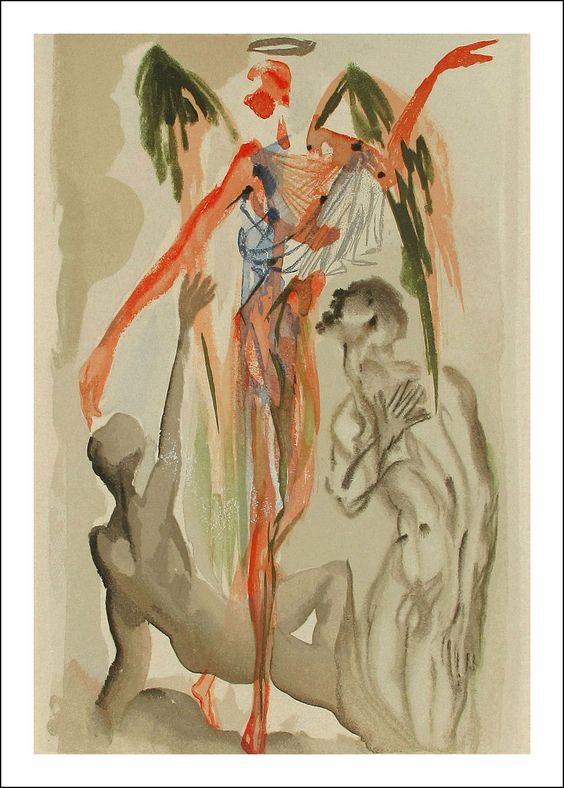

There is a recognition in Dante the Poet that once we have the image of God impressed upon us, it never leaves us, and brings all the different parts of our being together. When our life runs out, the incarnational unity “both human and divine” that is a child of God, does not diminish.

79 'When Lachesis runs short of thread, the soul

Quando Làchesis non ha più del lino,

80 unfastens from the flesh, carrying with it

solvesi da la carne, e in virtute

81 potential faculties, both human and divine.

ne porta seco e l'umano e 'l divino:

And the creative impulse that was in the Creator, passed on to us, remains as well, needing to be fulfilled, redeemed and celebrated.

82 'The lower faculties now inert,

l'altre potenze tutte quante mute;

83 memory, intellect, and the will remain

memoria, intelligenza e volontade

84 in action, and are far keener than before.

in atto molto più che prima agute.

Hence, our grief at betraying others is keener on Mt. Purgatory than it was while we were still alive, and our joy at being in the divine Presence is more profound than any experienced in worship ‘on earth.’ But it all comes back to being ONE; body, mind and spirit/soul. I find this profoundly parallel to my own experience, not only within my own life, but also within the 40 years of pastoral presence, teaching at the graduate level and spiritual direction. What one does with the body affects the soul. How one views and experiences the growth of depth of spiritual maturity and integrity dictates the choices one makes as to bodily choices. This is not just about choices of sexual partners, it is far deeper than that: where and with whom one chooses to travel through life, what one decides to take on as a vital realm of activity and sacrifice, the choice of response to suffering within one’s own self as well as injustice within society. It seems to me that these choices and responses may indeed continue on in and through this life, as well as into eternity. Indeed, John Donne got it right: “No man is an island…”

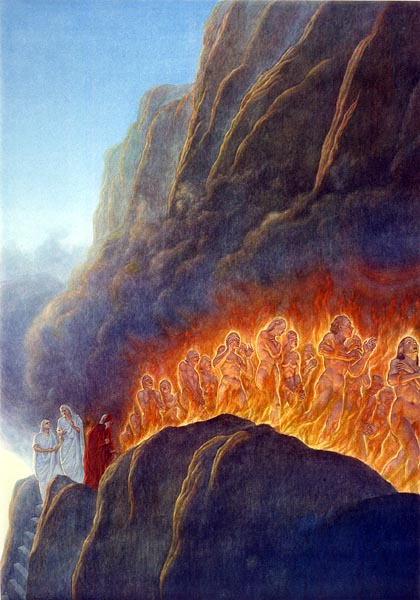

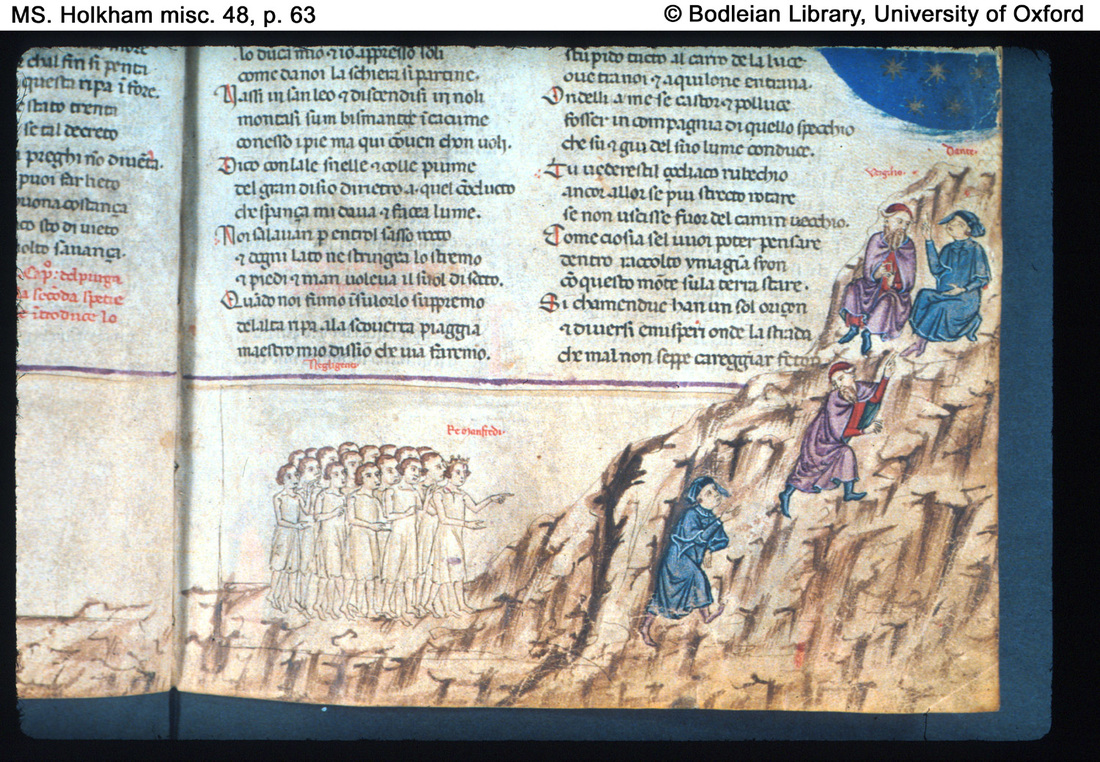

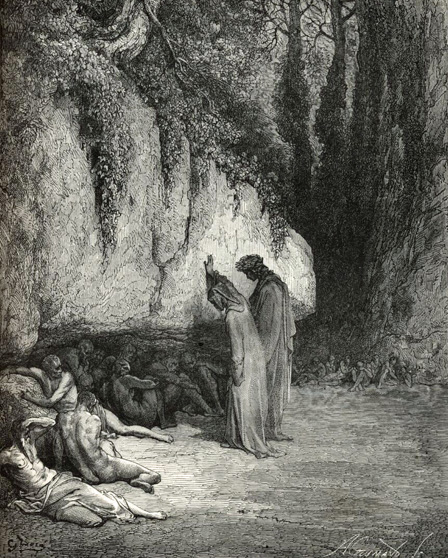

Moving on, we come to the final level, where Lust is cleansed from the shades by a raging fire. The path is indeed a narrow one, between a wall of flame and the precipice.

112 There the bank discharges surging flames

Quivi la ripa fiamma in fuor balestra,

113 and, where the terrace ends, a blast of wind shoots up

e la cornice spira fiato in suso

114 which makes the flames recoil and clear the edge,

che la reflette e via da lei sequestra;

115 so that we had to pass along the open side,

ond' ir ne convenia dal lato schiuso

116 one by one, and here I feared the fire

ad uno ad uno; e io temëa 'l foco

117 but also was afraid I'd fall below.

quinci, e quindi temeva cader giuso.

118 My leader said: 'Along this path

Lo duca mio dicea: "Per questo loco

119 a tight rein must be kept upon the eyes,

si vuol tenere a li occhi stretto il freno,

120 for here it would be easy to misstep.'

però ch'errar potrebbesi per poco."

Here they cannot gawk and gaze as they meander along. But of course, at deeper levels we find this to be true as well. Matthew mentions it: Matthew 7:13-14 “Enter by the narrow gate; for wide is the gate and broad is the way that leads to destruction, and there are many who go in by it. 14 Because narrow is the gate and difficult is the way which leads to life, and there are few who find it.”

This is true in the overall life of faith, for Dante the Pilgrim obviously lost his way on the narrow path in Inferno 1, line 1 “Midway in our life’s journey, I went astray…” But it also applies to this level specifically, the level of Lust. The sin of lust obviously enters first through the eyes. We see that immediately in the Petrarchan style of poetry and Dante the Poet recognizes that himself, for it was this simplest and most immature level of attraction that first drew him to Beatrice. And we return, yet again, to the fact that what we do, at almost any level of being, matters not only to ourselves and others, but also to the integrity of our spiritual being and the wholeness of society and God’s creation. What we do in Vegas does NOT stay in Vegas.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed