PRELUDE

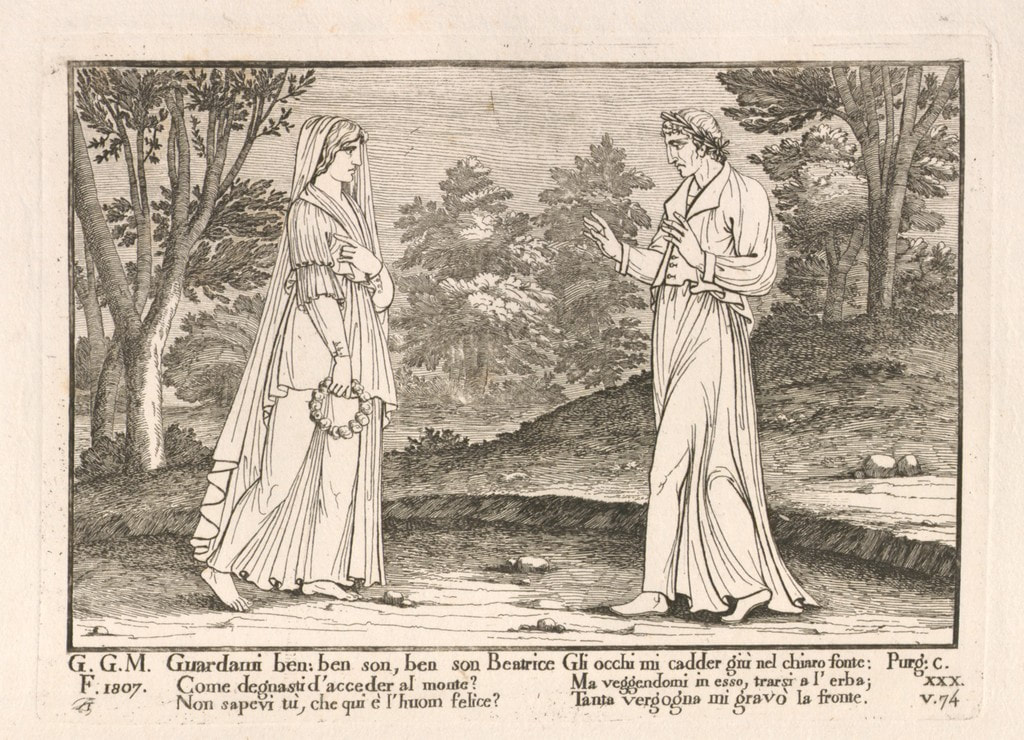

Verses 1 to 21 give us the joyous preparation for the appearance of Beatrice. One of the figures in the parade of the history of the church sings out from the Song of Songs “Come, Bride of Lebanon!” and everyone echoes that call. It is done three times, followed by a chorus of Hallelujahs.

19 All were chanting: 'Benedictus qui venis' and,

Tutti dicean: "Benedictus qui venis!"

20 tossing flowers up into the air and all around them,

e fior gittando e di sopra e dintorno,

21 'Manibus, oh, date lilïa plenis!'

"Manibus, oh, date lilïa plenis!"

We have here preparation with scripture, psalter and sung prayers of the church. There is a sense of energetic joy and excitement that includes such a fury of the tossing of flowers up into the air that it becomes a “cloud of blossoms” from which Beatrice will appear. Surely your commentary will tell you that verse 21 is from the Aeneid, meaning “Give lilies with full hands” and it occurs at a funeral. And yet, here, we have a little “OH” tucked in the middle of the phrase that gives it an emotional twist. The lilies here can be applied to the Bride of Lebanon who will be the “Lily of the Valley,” so there is anticipation and celebration in its meaning. While we will soon find that this may be the very time when Virgil leaves the scene, unbeknownst to Dante the Pilgrim, and so the quote from Virgil’s Aeneid featuring the loss of a loved one is completely fitting as well. That one verse, that one little “OH” carries a world of anticipation and grief and hope!

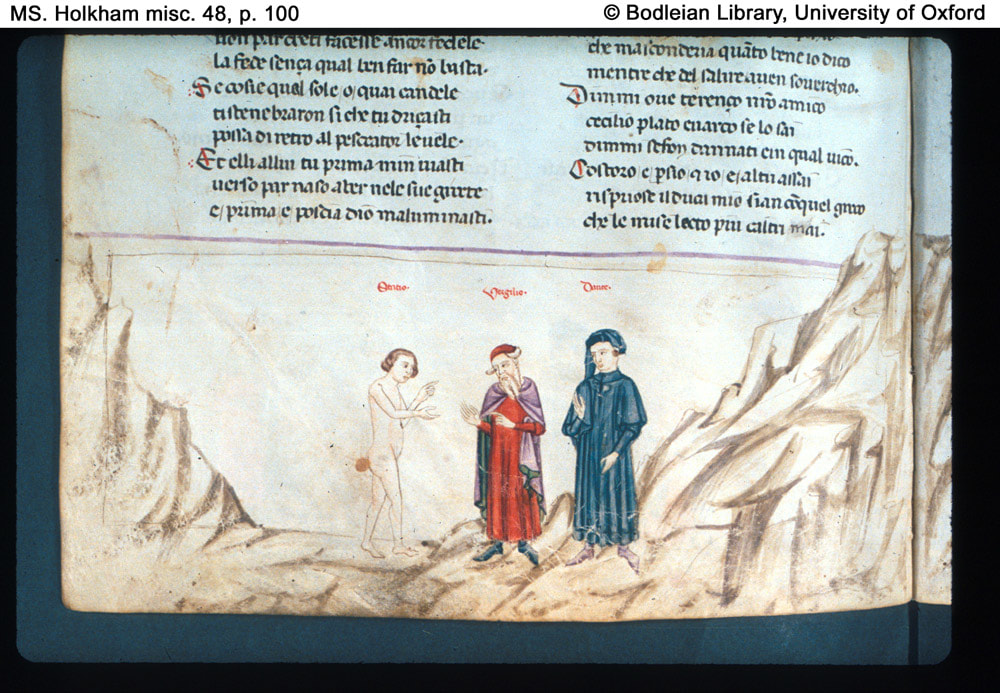

Please note some remarkable examples of Dante’s symmetry in the Commedia: in the same canto that Beatrice appears, Virgil disappears. We are in Purgatorio 30, but then in Paradiso 30, Beatrice disappears. She will have been in the Commedia for 33 cantos. Comes a time to move from one mentor to the next. Do not weep over the last one, but rejoice in the next. We also have a variety of emotions in this canto: singing, praising, full-on weeping at the loss of Virgil, full-on disapproval by Beatrice with subsequent scorn and lecture. In fact, we have here in Purgatorio 30, more terms used for tears and weeping than any other canto in the Commedia. Indeed, there is even a shift in the gender of his mentors and guides. He turns toward Virgil as “a child running to his mamma” only to find empty air, while Beatrice appears out of empty air with a masculine “Blessed is HE who comes” in vs. 19. This is the quote from the Gospel of Mark for Christ. Virgil disappears as the loving maternal presence and Beatrice flashes onto the scene as the Christ figure Himself.

And not only that, Beatrice continues this strong, male presence, telling Dante the Pilgrim not to weep… YET. And definitely not to weep for the loss of his ‘mamma’ Virgil. There is still a battle to be won and work to be done!

55 'Dante, because Virgil has departed,

"Dante, perché Virgilio se ne vada,

56 do not weep, do not weep yet--

non pianger anco, non piangere ancora;

57 there is another sword to make you weep.'

ché pianger ti conven per altra spada."

58 Just like an admiral who moves from stern to prow

Quasi ammiraglio che in poppa e in prora

59 to see the men that serve the other ships

viene a veder la gente che ministra

60 and urge them on to better work,

per li altri legni, e a ben far l'incora;

Beatrice speaks his name for the one and only time in the entire Commedia, “Dante… do not weep...” YET. We are now moving out of the Rational faith and guidance of Virgil to the realm of Repentant faith and surrender of Beatrice, through whom Christ guides Dante the Pilgrim. She uses his name but once, but that shocks him enough that the tears stop, even though his cheeks remain moist from them.

As with the Confessions of Augustine and the Consolation by Boethius, reflection and meditation upon one’s past life can reveal deep and profound truths. Beatrice helps him discover these truths, and what must be purged. Dante the Pilgrim discovers now that his heart has, in fact, been packed with ice and snow all around. Beatrice’s fierce gaze and stern countenance upsets not only Dante, but the angels as well.

94 but, when their lovely harmonies revealed

ma poi che 'ntesi ne le dolci tempre

95 their sympathy for me, more than if they'd said:

lor compartire a me, par che se detto

96 'Lady, why do you torment him so?'

avesser: "Donna, perché sì lo stempre?"

97 the ice that had confined my heart

lo gel che m'era intorno al cor ristretto,

98 was turned to breath and water and in anguish

spirito e acqua fessi, e con angoscia

99 flowed from my breast through eyes and mouth.

de la bocca e de li occhi uscì del petto.

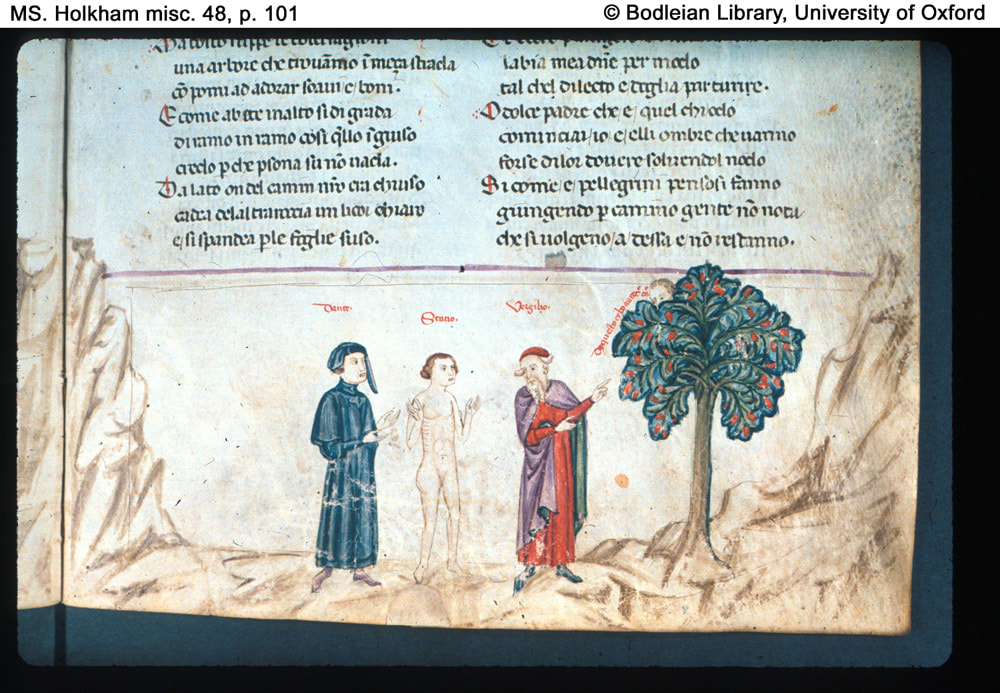

There will be no progress or healing, there will be little revelation in Paradise until Dante the Pilgrim surrenders completely, repents fully, and is remade, is born again. In a recent Bible study I attended, I was reminded of a Jewish rabbi, (was it Hillel?) who was approached by a student who asked the question; “Rabbi, why does the Torah tell us that the Almighty, Blessed be He, places His Word upon people’s hearts and not within them?” The rabbi responded “The Word of God can only be placed upon the heart. It is when the heart breaks that the holy words fall inside and we discover God’s truth.” Dante is now having his heart broken so that the truth can enter in. We read of his failings, his forgetfulness and his wandering in this incredible canto. He must be broken before he can be made anew.

142 'Broken would be the high decree of God

Alto fato di Dio sarebbe rotto,

143 should Lethe be crossed and its sustenance

se Letè si passasse e tal vivanda

144 be tasted without payment of some fee:

fosse gustata sanza alcuno scotto

145 his penitence that shows itself in tears.'

di pentimento che lagrime spanda."

Dante the Pilgrim is learning that his secular good that was embraced in Virgil’s writings and guidance must all now bring him to the place where everything is surrendered to the eternal good. He begins to see now, that God’s hand has been in all that brought him here, and he, Dante the Pilgrim, but fully release all his desires and pride, he must take full part in this purgation. We will see in the rest of the Purgatorio where that will lead him and how that will create the New Man in him. This is the deep logic of true faith.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed