Even though I have read this Canto at least seven times over the span of 30 years, I am still flummoxed, and truthfully, bored by two thirds of it. In my opinion, the academic [read PEDANTIC] descriptions of the state of the soul, which in reality is Plato vs. Aristotle and Aquinas, add almost nothing to the Commedia and the current journey up the side of Mount Purgatory. Add to that the convoluted scientific / mythic [read EVEN MORE PEDANTIC] descriptions of the sun’s position and the angle of the equator and we have, in one sense, Dante the Poet showing off his incredible knowledge. I find it almost as mind – numbing as reading the poetry of Ezra Pound or Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. [Read here ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZ…]

And yet, hidden within this Canto are a few jewels of discernment as well as a marvelous admission at the end of Dante the Poet’s own pride and a puncturing of that in the final, delightful conversation with Belacqua.

Upward Bound

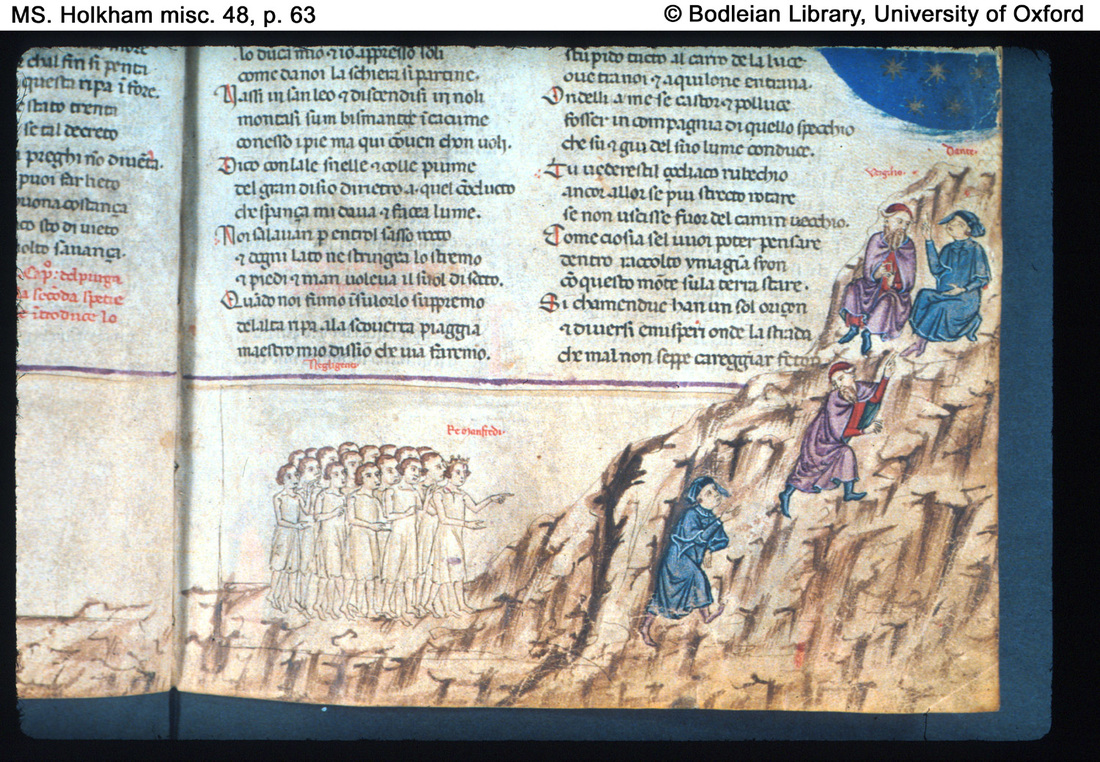

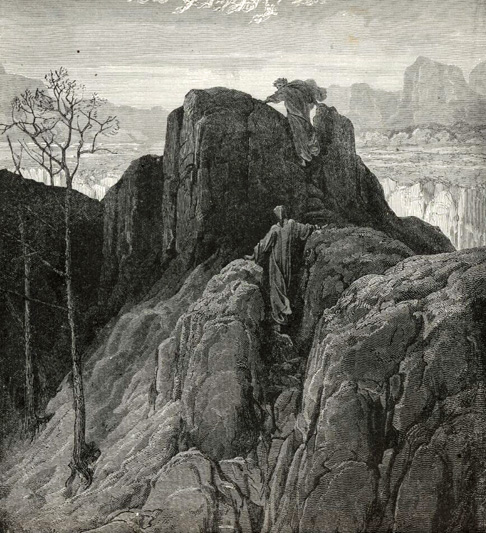

One such jewel which we will encounter time and again, especially as Dante the Pilgrim journeys through Purgatory, is the necessity of striving and single minded dedication. He tells us that he is in need of flight because the way up Mount Purgatory, is worse than any trail on earth. Indeed, it looks impossible.

25 One may go up to San Leo or descend to Noli

26 or mount to the summits of Bismàntova or Cacùme

27 on foot, but here one had to fly--

But then, almost with unnecessary oversimplification, we are told that flight is really just a metaphor describing the desire to live and walk in the spiritual way.

28 I mean with the swift wings and plumage

29 of great desire, following that guidance

30 which gave me hope and showed me light.

| Yet, this is no easy journey, and because Dante the Poet uses the image of rock climbing, in today’s sporting daredevil culture, that rings even more true than ever. We get it. 31 We climbed into a fissure in the rock. 32 The stony walls pressed close on either side. 33 We had to use our hands to keep our footing. 34 When we had reached the crag's high upper ledge, 35 out on the open hillside, 'Master,' I said, 36 'which path shall we take?' 37 And he to me: 'Do not fall back a single step. 38 Just keep climbing up behind me 39 until some guide who knows the way appears.' |

43 Exhausted, I complained:

44 'Belovèd father, turn around and see

45 how I'll be left alone unless you pause.'

46 'My son,' he said, 'drag yourself up there,'

47 pointing to a ledge a little higher,

48 which from that place encircles all the hill.

49 His words so spurred me on

50 I forced myself to clamber up

51 until I stood upon the ledge.

There were times in my three plus decades of pastoral ministry and fifteen years of teaching at the graduate level where it felt as though I were dragging myself, following the call, and believing that this was God’s work, even though it felt at times like crucifixion. Dante the Poet, and I also, have little patience with the Pollyanna view of an ever-smiling pilgrim doing God’s good work with no pain, no doubts, no tears, no cross.

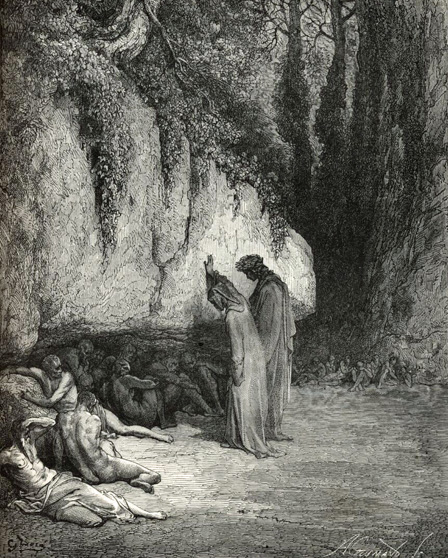

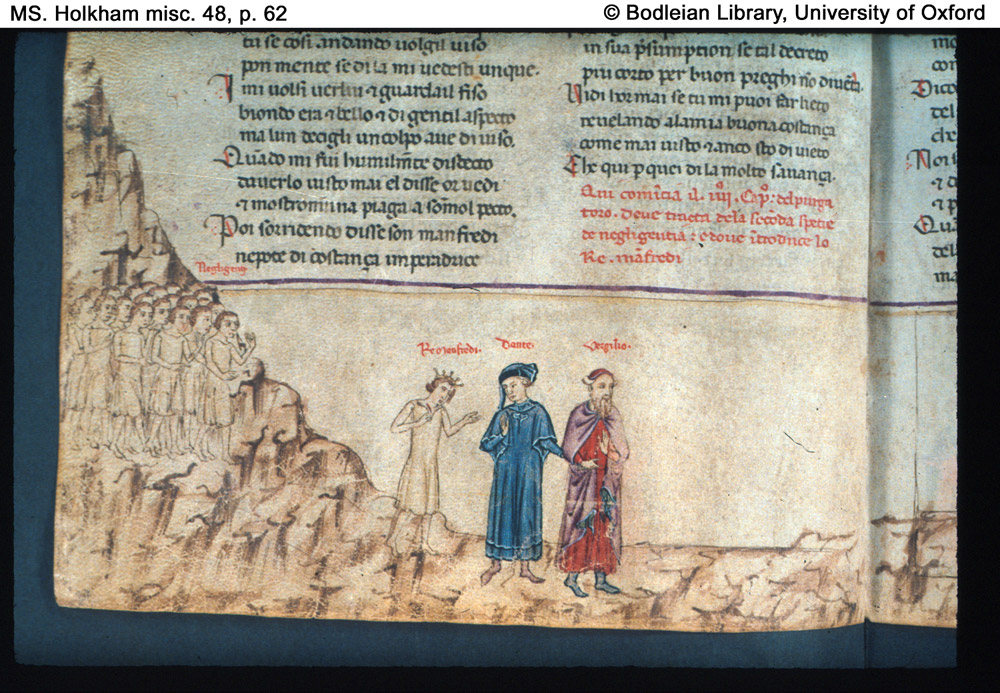

And here we have Dante the Poet relieving the pedantic descriptions and the fierce striving and sacrifice with a bit of self – critique and humor. The great desire for Dante the Pilgrim to sit and rest is remarked upon by his old friend Belacqua, who not only chides him about resting but also comments on the extended commentary about the sun’s journey [I imagine him doing so with a yawn and a wry smile…]:

98 a voice close by called out: 'Perhaps

99 you'll feel the need to sit before then…'

119 to say: 'Have you marked how the sun

120 drives his car past your left shoulder?'

The dear dialogue between the two is fresh, authentic and comes from their actual shared friendship. Yes, there is a sense of urgency still in Dante the Pilgrim’s journey but there is time too, for shared celebration in Belacqua’s salvation, however muted by subtle humor and repartee. It is a lovely, knowing end to a Canto that began with self-referent showing off of philosophy and scientific theories.

Still and all, Virgil knows the true priorities what this journey is all about; saving Dante the Pilgrim’s soul. He brooks no more delay: time to move on.

136 And now, not waiting for me, the poet began

137 to climb the path, saying: 'Come along.

138 Look, now the sun is touching the meridian,

139 and on Morocco's shore night sets her foot.'

Only in Purgatory are we guided by time: it is crucial to keep moving while it is day. We will find soon enough, that the quotidian perspective rules this realm.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed