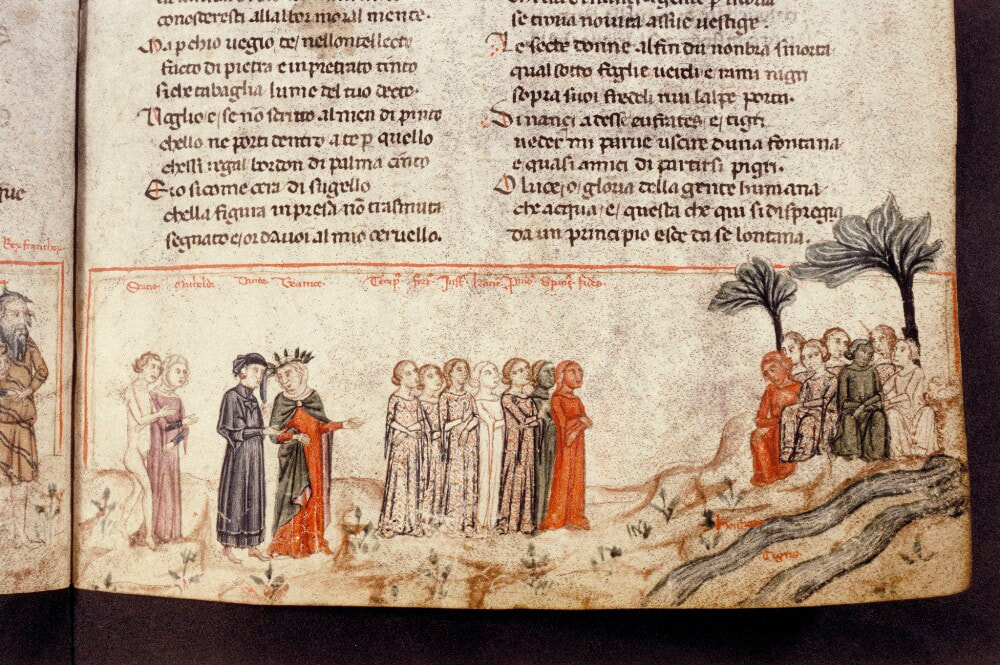

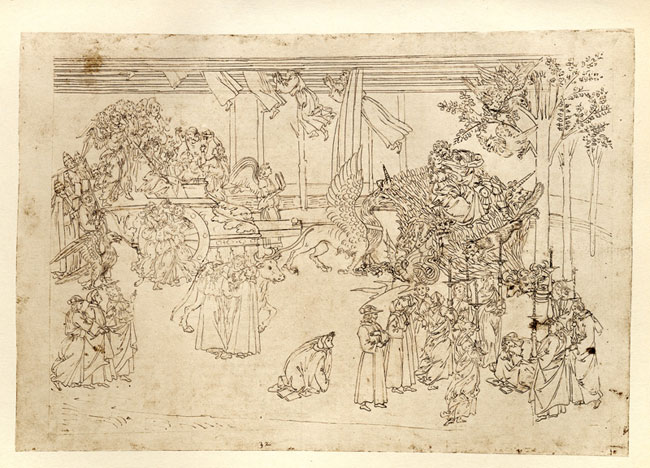

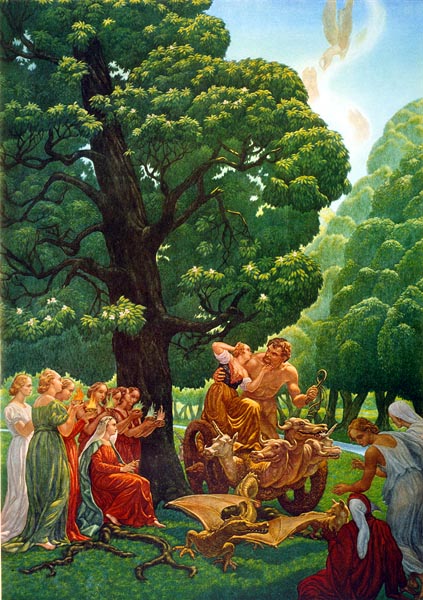

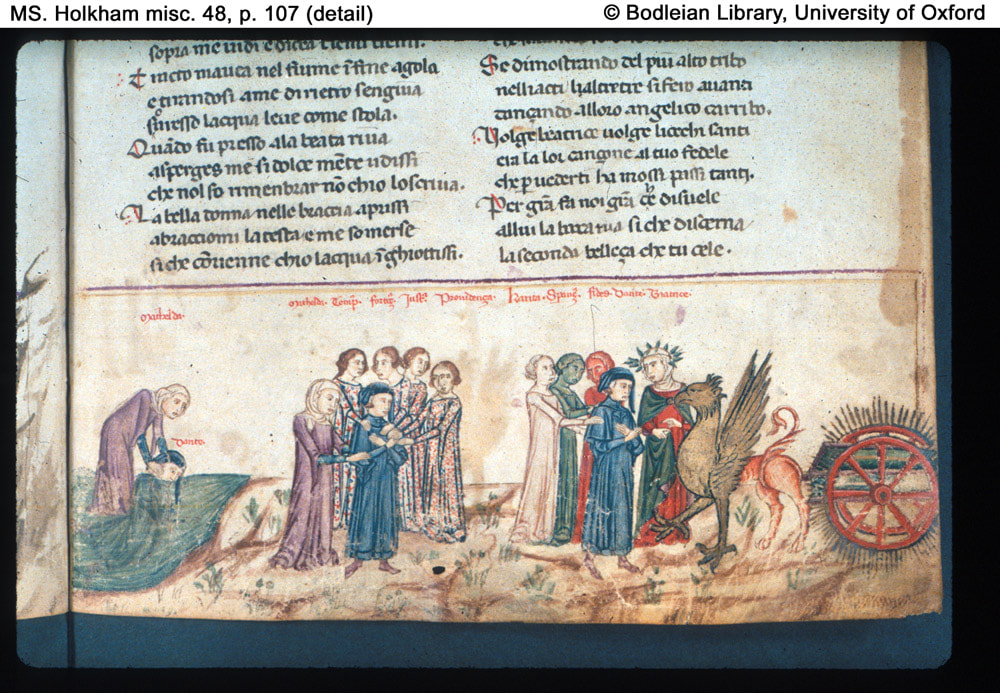

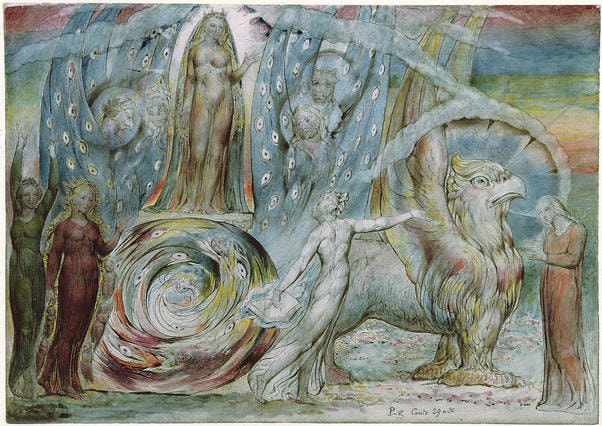

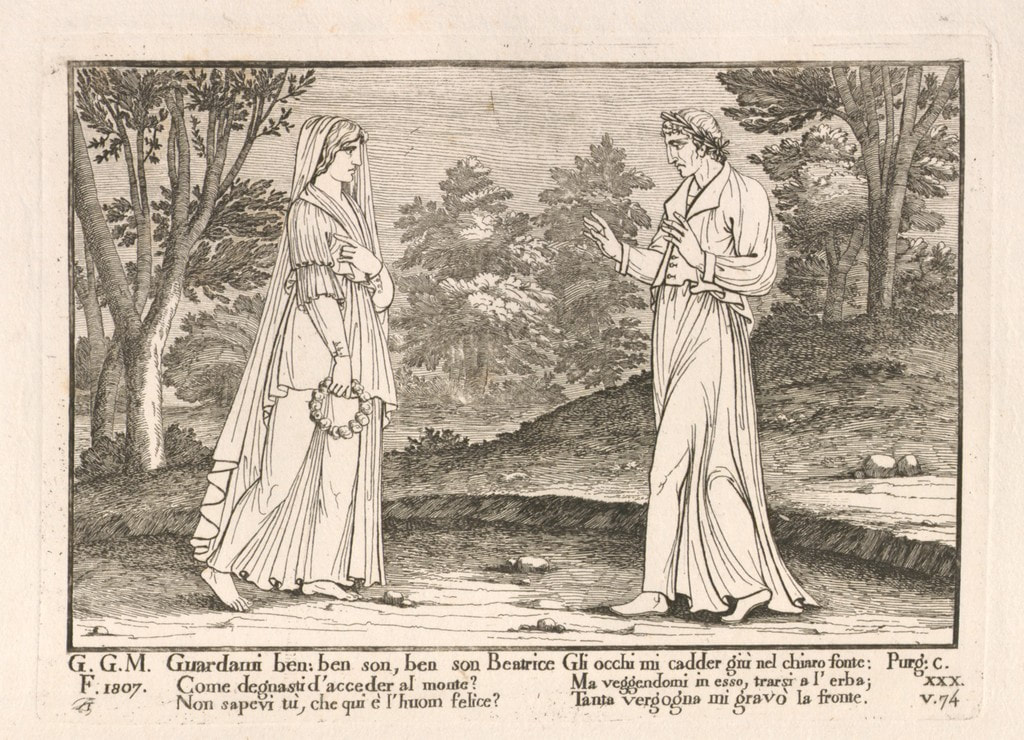

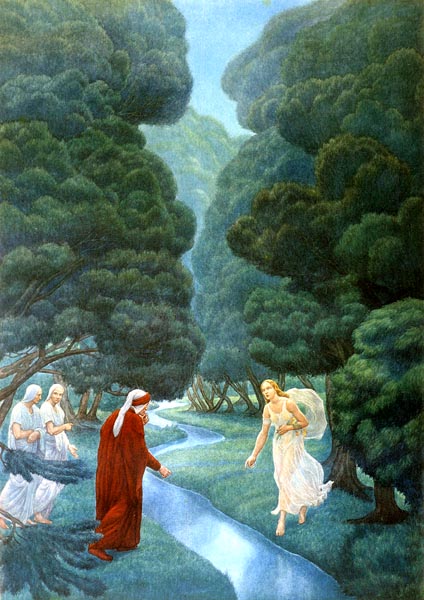

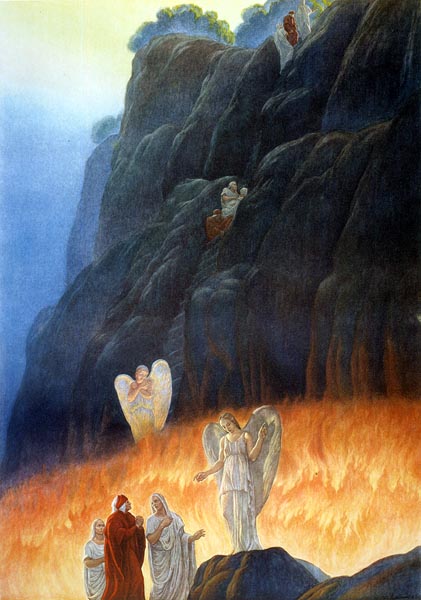

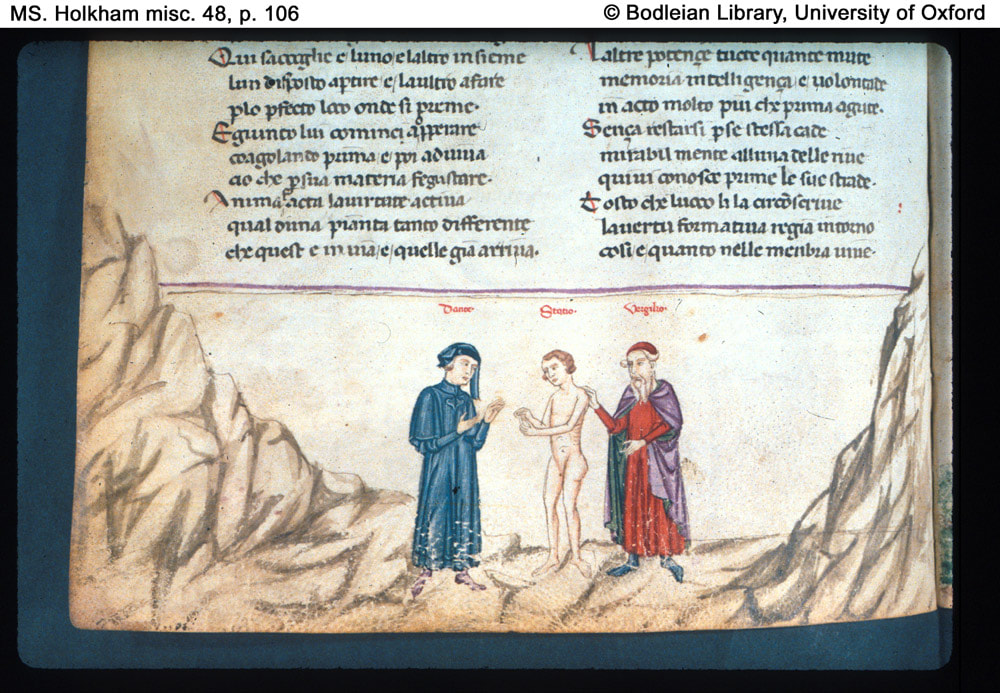

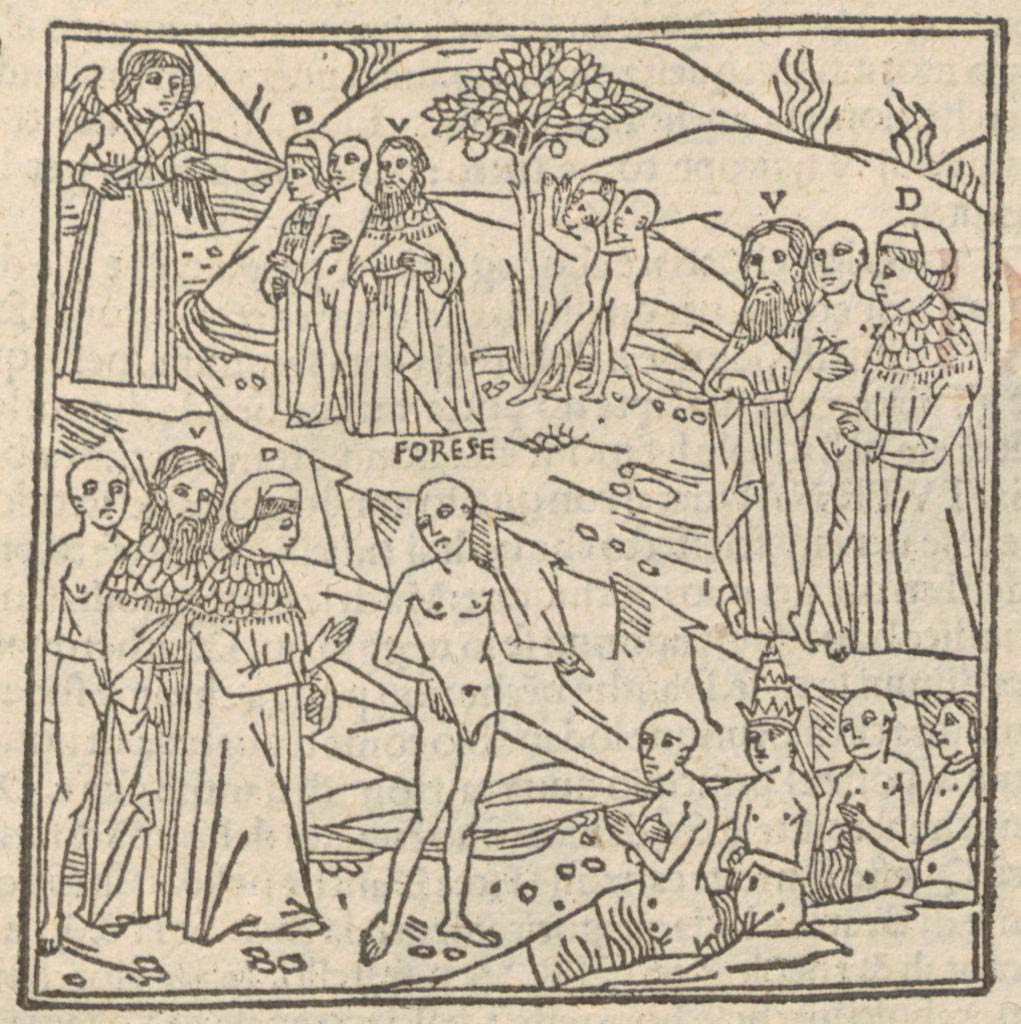

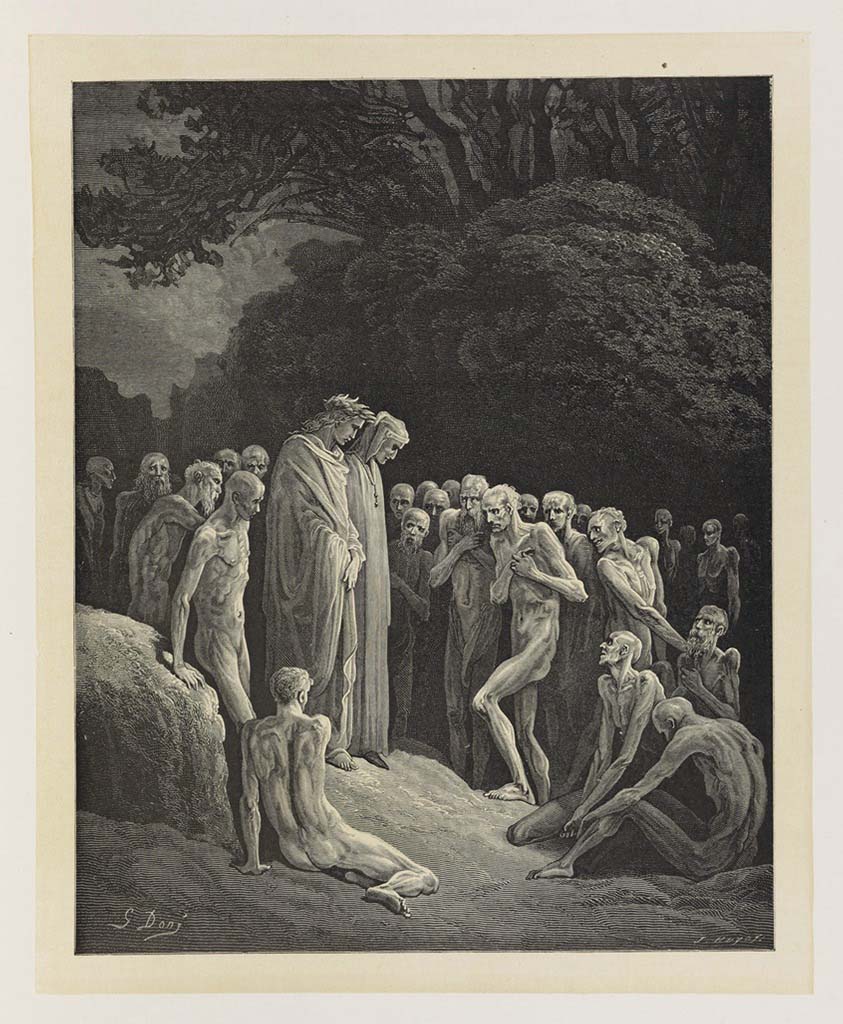

All singing, dancing, allegorical drama and final preparations come to an end as Dante is prepared for Paradise, guided now by Beatrice. Dante has discovered on the long journey up the Seven Storey Mountain that with God and Beatrice, what is most hurtful and painful was not the fact that Dante the Pilgrim had broken God’s Laws, but that he had broken God’s heart, along with Beatrice’s as well. What is being restored on this long climb is relationship and trust. Unlike the souls in Hell who blame any and all for their suffering rather than accept their own part in their pain, Dante the Pilgrim has come to realize that he must own up, so to speak. He accepts that he has gone astray, and especially in these last few levels on the way to the garden, he must accept his part in it all. And he does, through confession, through baptism, through submission and penance and obedience he is now ready to move on toward Paradise. Hence, Beatrice now calls him ‘brother’ in this final Canto. Hence, she tells him it is now indeed time to stop being a tongue-tied, adoring star-crossed lover, but a serious student and, ultimately an equal child of God.

23 she asked: 'My brother, since we are together,

dissemi: "Frate, perché non t'attenti

24 why do you not dare to ask me questions?'

a domandarmi omai venendo meco?"

Dante the Pilgrim mumbles something along the lines of… “Ummm, aw, shucks, you know what I’m like.” But Beatrice will have none of it:

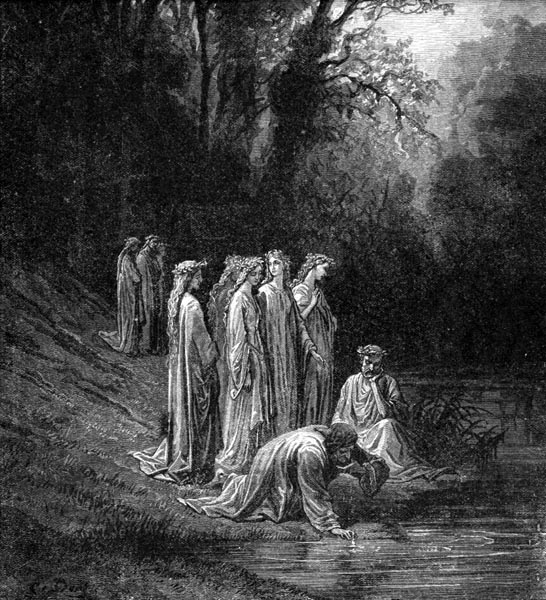

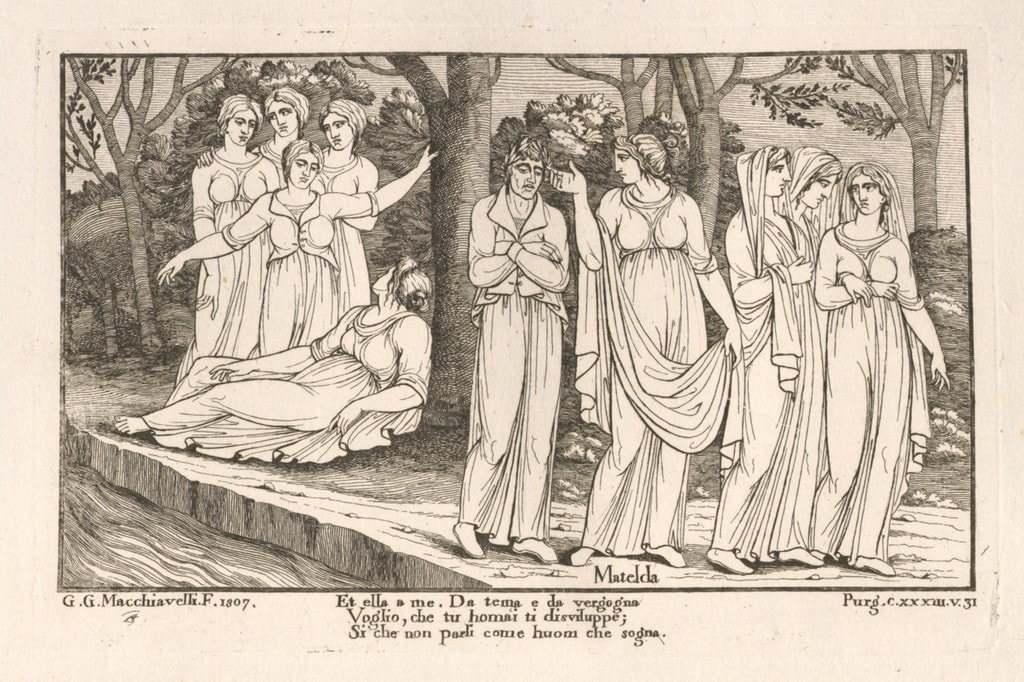

31 And she: 'Free yourself at once

Ed ella a me: "Da tema e da vergogna

32 from the snares of fear and shame,

voglio che tu omai ti disviluppe,

33 no longer speaking as a man does from his dream.

sì che non parli più com' om che sogna.

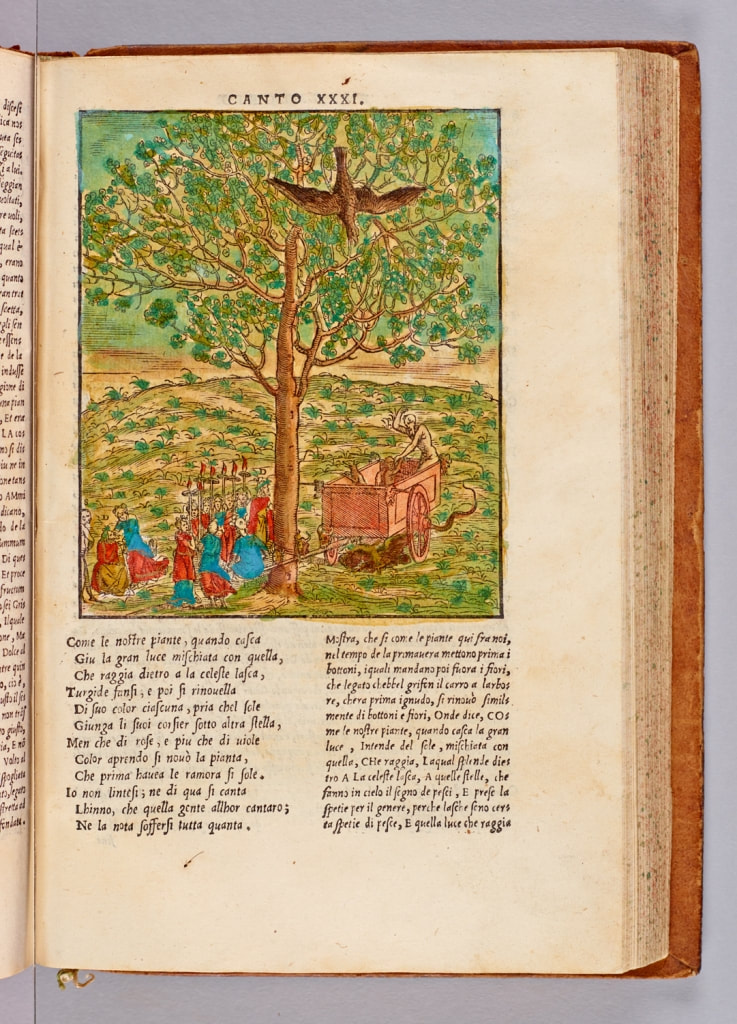

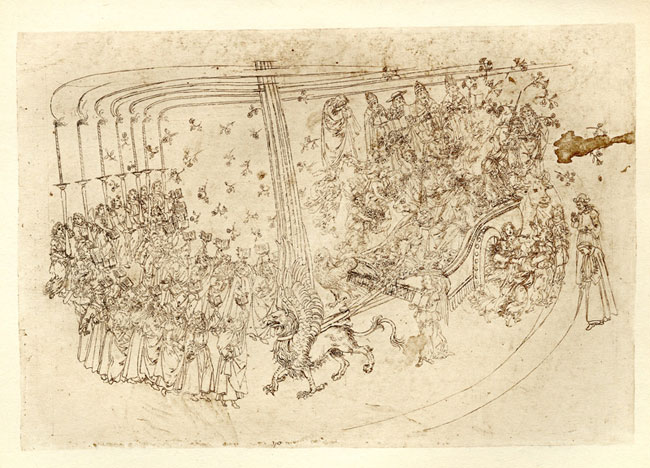

Beatrice reminds him that his part in all this is to let others know all that he experiences and is taught. If all the words and theology seem too much, then he is to hang on to the images and share them, at least. Here is the medieval reality that images and imagination can teach as profoundly as lectures and word-study. Dante, the POET, agrees that the least he can do is keep those images fresh. Even so, Beatrice tells him she will try to make it all as plain as possible for the sake not only of Dante the Pilgrim’s soul, but to renew the church as a whole.

100 'But from now on my words shall be

Veramente oramai saranno nude

101 as naked as is needed

le mie parole, quanto converrassi

102 to make them plain to your crude sight.'

quelle scovrire a la tua vista rude."

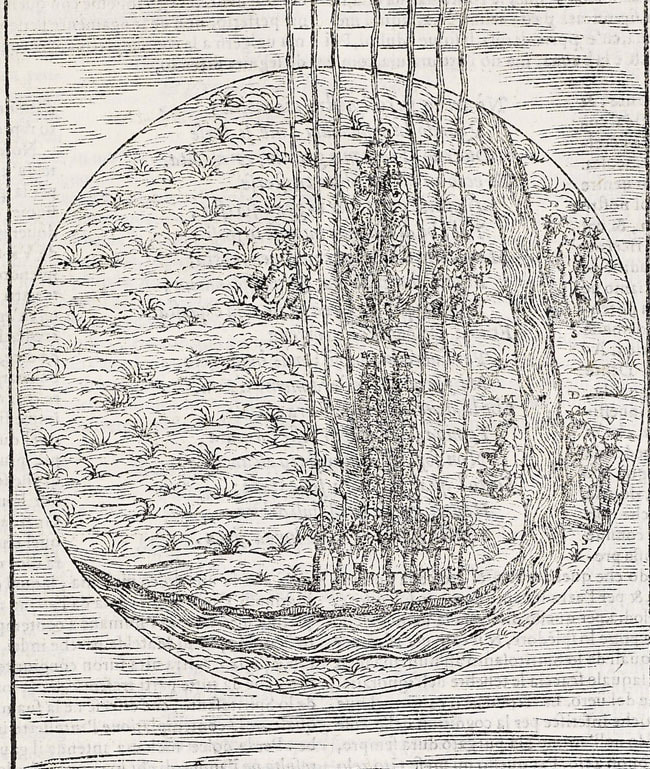

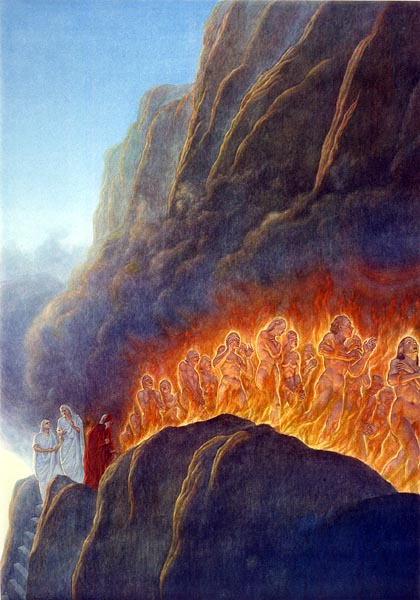

The second drink / baptism of Dante the Pilgrim restores the memories of his sins, but without the shame and grief they originally inflected upon him. Here we finally have the redemption of the Fall. This indeed has become the “Happy Fall” or trip, which ended up falling into the arms of Christ. After the lessons of Grace, we see that even the most hurtful and shocking betrayals can be redeemed. Think of Peter being asked three times by the risen Lord, “Peter, do you love me?” Think of Dame Julian of Norwich meditating on the bleeding Christ of the Passion for three decades. Out of that comes her stunning affirmation: “All shall be well and all shall be well and every manner of thing shall be well.” This is not an airy-fairy promise that nothing bad will ever happen, but rather it is a realization that God’s love will encompass us and the Lord’s presence will be with us regardless of the exigencies of experience and this life on earth. Dante, in exile from his beloved Florence, knows this as well, and will assure his readers of the same. One way he does it is in the lovely little motif / promise that God’s stars will ever be calling us further. In fact, he ends each section; the Inferno, the Purgatorio and the Paradiso with that one word: STARS.

The Inferno:

136 we climbed up, he first and I behind him,

salimmo sù, el primo e io secondo,

137 far enough to see, through a round opening,

tanto ch'i' vidi de le cose belle

138 a few of those fair things the heavens bear.

che porta 'l ciel, per un pertugio tondo.

139 Then we came forth, to see again the stars.

E quindi uscimmo a riveder le stelle.

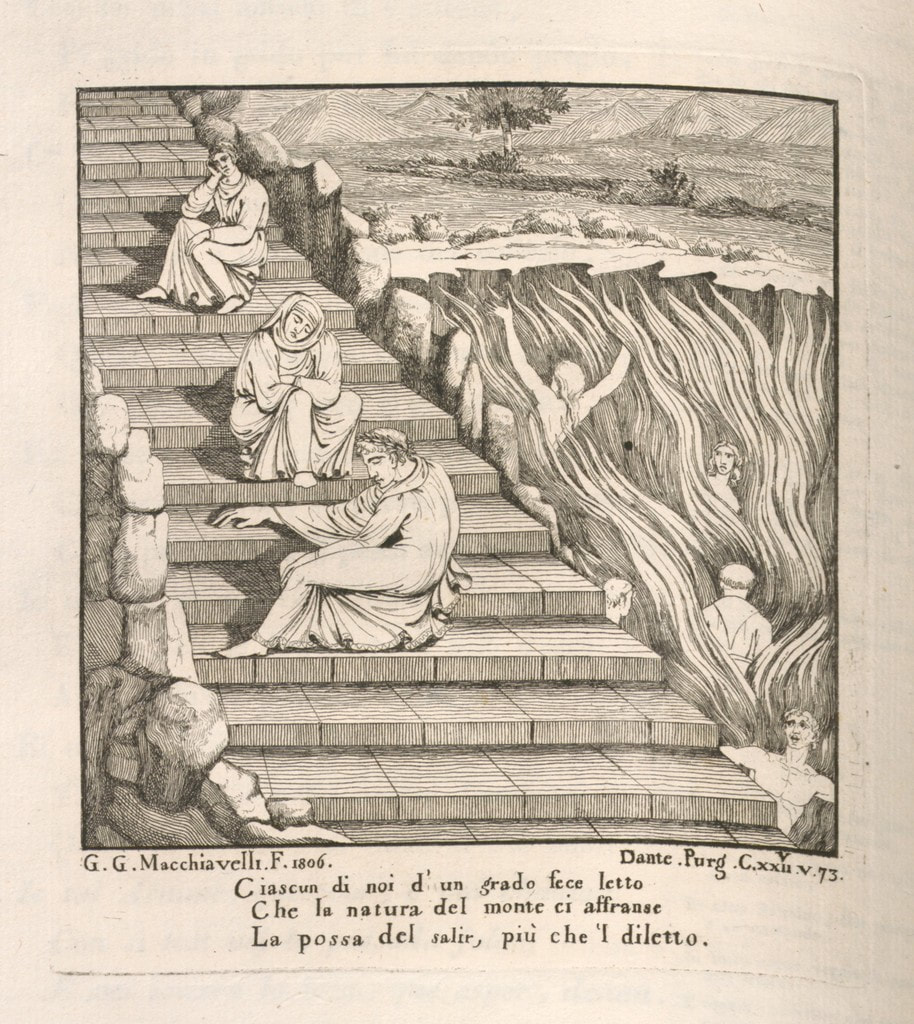

In the Inferno, he rises up after climbing the hairy shanks of Satan up into the night sky, set free once again to look and see the stars. Here, in the Purgatorio, he also rises up, renewed and redeemed ready to ‘rise up to the stars.’

Purgatorio:

142 From those most holy waters

Io ritornai da la santissima onda

143 I came away remade, as are new plants

rifatto sì come piante novella

144 renewed with new-sprung leaves,

rinovellate di novella fronda,

145 pure and prepared to rise up to the stars.

puro e disposto a salire a le stelle.

Truth to tell, I am reading Dante’s Commedia non-stop, and have done so since the early 1970’s, when I discovered it in my Medieval Literature course in college. I’ve forgotten how many times I’ve read it, but I discover new lessons, beauty and insights into my own journey as I reread it. This time around it has come to me, forcefully, that Dante’s spiritual growth is profoundly incarnational and holistic. Space, movement, singing and sleeping all play as important a part in his redemption and spiritual growth as memory and beauty and poetry and scripture. Personal integrity and spiritual growth is not only what happens in our hearts but it also matters what we do with our hands. Hence, those who only read parts of the Inferno when it comes to Dante miss some of the finest insights and best poetry and wisest guidance toward spiritual and personal wholeness by neglecting the Purgatorio and Paradiso.

At the bottom of Hell he is in a literal sense as far from God as it is possible to be [remember the medieval world view]. At the top of Mt. Purgatory he is as far above the work-a-day political world of Florence as it is possible to get while still on earth. And now, like the tree itself in the garden, he is renewed, refreshed “with new-sprung leaves” and looking up toward this next stage. It is only right. At some point in one’s own spiritual journey, great things are expected and excuses are no longer accepted. If one is to be a follower of Christ, then gird up thy loins, pick up thy cross and follow wherever He leads. One must grow into maturity emotionally, physically, spiritually and courageously. That is what will be needed as, with Dante the Pilgrim, we step up into realm of the highest heavens. Join Me!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed